×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

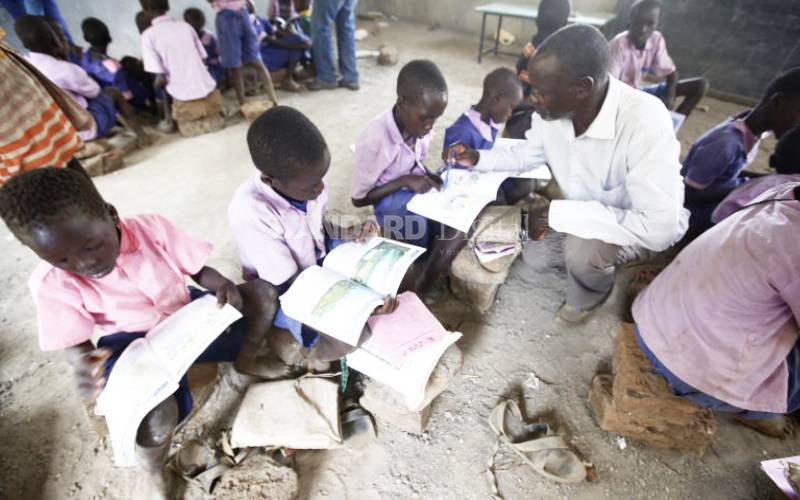

Paka Hills Primary School. [Kipsang Joseph, Standard]

It is going to noon and Grade 3 at pupils at Paka Hills Primary School in Baringo County are in for environmental studies.