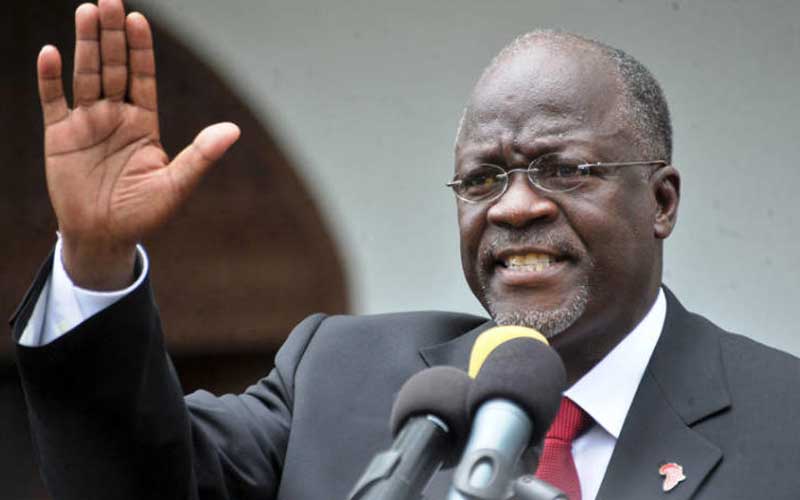

Viewed as a reformer when he took power in 2015, Tanzania's President John Magufuli (pictured) now faces mounting accusations of intolerance to criticism and illegal repression of opponents, which risks blighting his image. The latest in a growing list of concerns is the recent enactment of a law that severely restricts the freedom of association by cracking down on non-governmental organisations. The law was enacted hurriedly and with little consultation, after debate on its contents was certified as urgent, using a procedure that analysts say has no precedent in Tanzanian legislative history and which they have described as unconstitutional.