×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

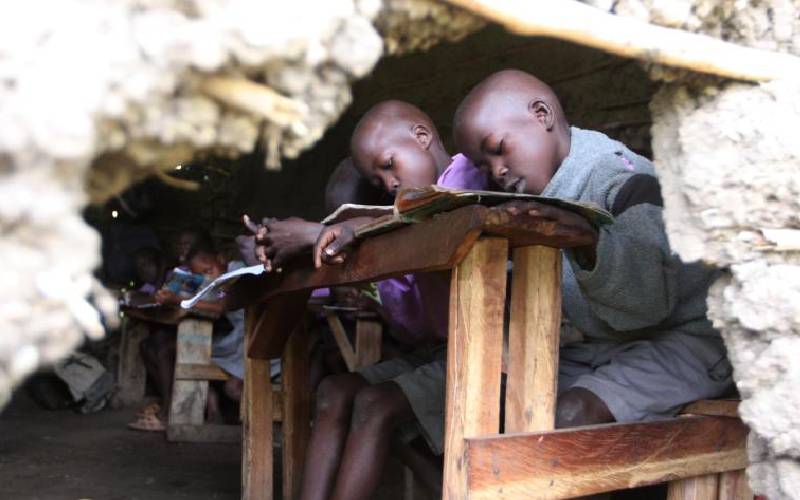

Standard Four pupils of Cheptuyet Primary School in Muhoroni, Kisumu County. [Collins Oduor, Standard]

To some Kenyans, not paying school fees for their children is not an issue. However, a larger percentage of Kenyans, majority of whom hardly manage a balanced diet, sweat to pay school fees. Things get worse when a child goes to university.