×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

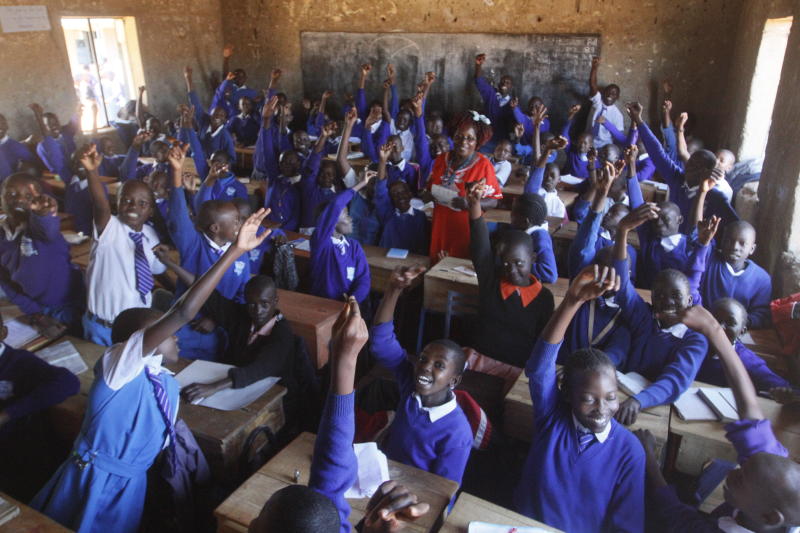

Kenyans, including teachers, have since 1964 embraced reforms in education. Unfortunately, education reforms in Kenya have consistently been plagued by the reformers’ (in particular, senior ministry officials, State agencies and teachers’ unions) lack of knowledge and appreciation of the history of education.