×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

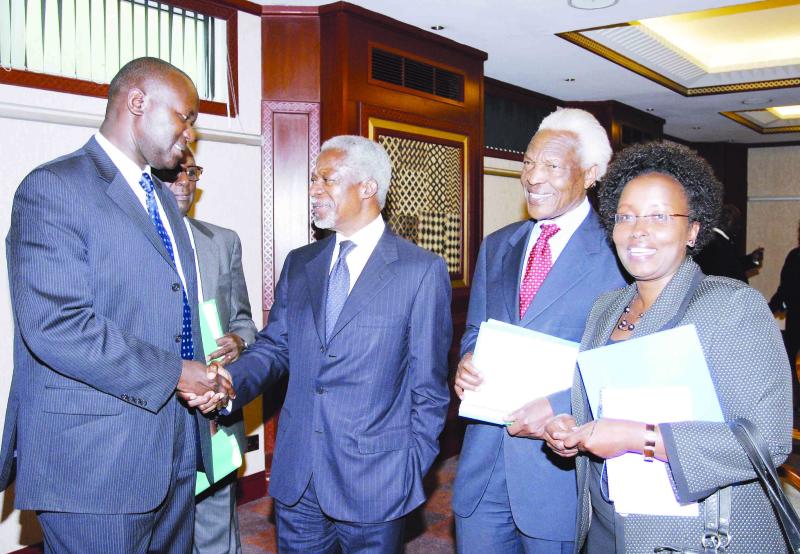

On a grumpy Wednesday morning, April 14, 2010, Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commissioners gathered around their conference table to give their stubborn chairman Bethuel Kiplagat a piece of their minds.

Two days before, Kiplagat had snookered them “live” in front of television cameras, reneging on an earlier deal to “step aside” from the commission. It was now eight months since they had been sworn in but had not moved an inch because debate on credibility of the old man had taken centre stage.