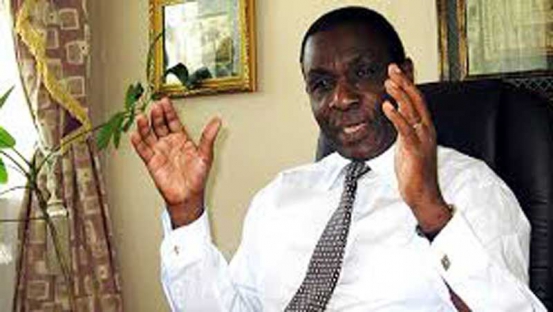

“I will have to make changes but first, I need to get rid of these thieves!” declared newly appointed Maseno University Vice Chancellor Prof Fredrick Onyango, pointing both hands to stunned senior academics and administrators sitting nervously behind him.

The deafening, ecstatic roar from students at Harambee Hall nearly drowned his second shocker. “And if they resist change, tutachapana!” the Physics Professor thundered, staring menacingly at his beleaguered colleagues as he pranced in a mock boxing spar with an imagined opponent.