|

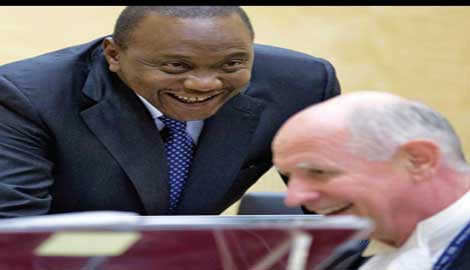

| President Uhuru Kenyatta speaks to his lawyer at ICC courtroom in the Hague |

When President Uhuru Kenyatta flew to The Hague recently for the status hearing of his case at the International Criminal Court (ICC) after ceding power for 48 hours, he might have missed his usual Presidential Lounge facility at JKIA.

But as the Kenya Airways aircraft (where he was flying First Class on a business flight) cut through the skies to Amsterdam, Uhuru might also have been grateful that it was not Lokitaung he was landing at – the way his father Jomo did on October 20, 1952, where he was held in custody until the decision to charge and try him was made by the British.