By Thiong’o Mathenge

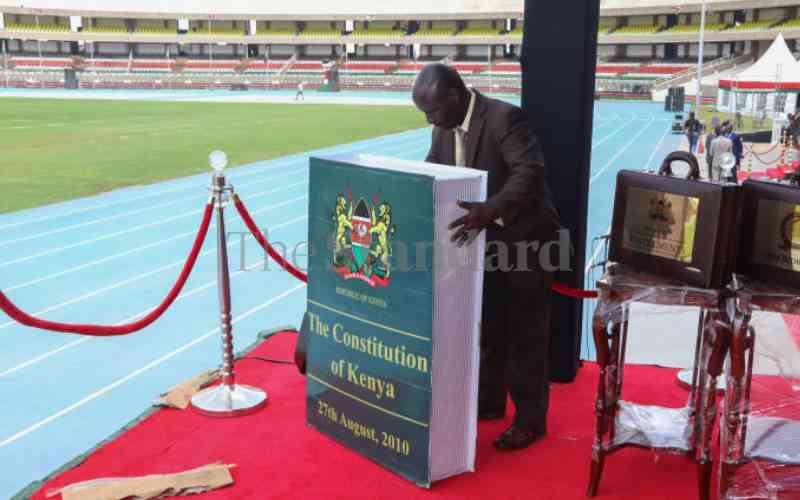

Kenya: The importance of the land sector in the national social-economic affairs is such that it boasts of a chapter in the Constitution (Chapter 5).

The progress made on land reforms on paper is impressive compared with other African and Third World countries.

First came the National Land Policy (Sessional Paper No 3 of 2009), then the Constitution (Chapter 5), a raft of new institutions key among them the National Land Commission (NLC), and a series of new laws, all in a short span of time by Kenyan standards.

The taxpayers money used to get this far, the lives lost, the bloodshed, property destroyed, national vexation and emotions expended in land-related conflicts are enormous.

Yet, every generation of political leaders in the name of cabinet ministers, aficionados, and other actors of consequence like the church, always seemed keen to massage public anxiety and dissipate expectations by making up illusions of motion without movement.

The latest scorecard by the most vocal lobby on land reforms, the Land Development and Governance Institute (LDGI), lauds progress made on paper, but laments little has been achieved in translating this to efficiency in service delivery.

Corruption was rampant, staff demotivated and slow, costs were high due to repeated visits to land offices, while brokers still reigned supreme in land transactions.

The 13th scorecard shared with the executive and released last month from a survey of 27 counties made a damning verdict:

“Gains made through the constitutional provisions, new laws and institutions, were yet to translate into efficient service delivery at the customer level. Land records were yet to be digitised, and registries automated to cut down on time and rising costs involved in travel and manual processes.”

The LDGI survey found the public was largely ignorant, and of progress made, therefore unable to demand accountability from government and avoid exploitation by officials and brokers.

Missed timelines

LDGI conducts national surveys on reforms progress and issues quarterly progress reports since the Constitution was promulgated.

As a voluntary gatekeeper, the LDGI scorecards have gained prestige, rallying public attention and outcry over missed timelines or sloppy drafting of land laws that resulted in pressure for redress.

Political goodwill to make real progress on land reforms seemed in short supply in the last three political regimes.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

A few examples would suffice illustration: To mollify the militant Mau Mau peasant class that offered its blood protesting the land dispossession by the British colonial government, the Kenyatta administration dangled a few settlement schemes to a few hundred peasants, with generous consideration for their leadership to tone down the rhetoric, before dumping the project all together.

The Moi administration pursued the same approach of sporadic settlement schemes to quell political agitation and appease the noisemakers.

When the noise about addressing the fundamentals got too loud to ignore, Moi set up the Njonjo Commission of Inquiry into Land Laws in late 1988, which made some substantial reform recommendations, but which no one read or gave a second look.

Kibaki’s first Narc administration came talking loud on land reforms, set up Ndung’u Commission of Inquiry on irregular land allocations, and the Prof Makau Mutua led-Task Force on Truth and Reconciliation Commission, both which captured impressive national sentiment and ground zero situation of the problem for the first time in modern Kenya.

A member of the TJRC Task Force, Prof Amukowa Anangwe, who had served the Moi/Kanu administration blissfully as cabinet minister, came out of the task force horrified after a whirlwind tour of the country:

“I had no idea, until now, how bitter, angry, divided and resentful Kenyans are on this land question.”

The Kibaki administration did not hear this, and the TJRC report was packed for safekeeping in some library.

Fast forward. After the post- election violence of 2007/08, land reforms ranked top of the list on the Agenda Four of urgent reforms to heal the nation under the National Accord and Reconciliation innovation aimed at ending the bloodshed.

However, Kibaki only gazetted the National Land Commission on the pain of a High Court order at the tail end of his term as president.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.