By Joe Kiarie

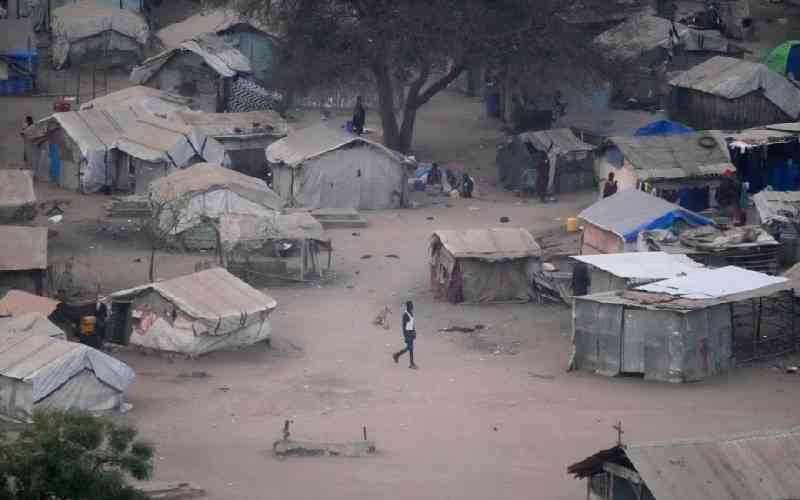

A few years back, they set on a journey into the unknown, leaving their jobs and families behind in pursuit of greener pastures miles away from home. The destination was the oil-rich South Sudan, which was enjoying a new lease of life after guns were dropped following a 21-year-old civil strife.

Despite the risks involved, the thousands of Kenyans setting camp up north were optimistic that with their country having steered the Sudan peace process and warmly sheltered refugees from Juba, the locals would reciprocate in kind.

But this conviction is fast proving to have been a fallacy, and the risks turning out to be real.

A worrying proportion of the over 70,000 Kenyans in South Sudan are now making the return journey in coffins. Their luckier colleagues are maneuvering the bumpy ride in tears, armed with shocking stories after being hounded out of multimillion-shilling investments by seemingly xenophobic locals.

Amid regrets, those who have returned home are painting a picture of a country steeped in anarchy, with locals and authorities capitalising on weak State presence to persecute vulnerable foreigners.

Today, businessman Patrick Jackona still curses the day he decided to invest in Juba. After investing millions of shillings in various sectors in South Sudan since 2001, he says he returned home empty-handed last year after being kicked out of his booming investments by a business partner.

The aviator says he and his three Kenyan partners lost Sh25.2 million in South Sudan after a local chased them off a joint investment. He says they registered a company in 2005 alongside a local lawyer and decided to put up aviation offices, a hotel and 15 fully furnished apartments.

“As the rules were clear that a foreigner could not own land, we got into an agreement with the lawyer that he buys the plot, which we were to acquire once the laws changed. He injected $10,000, while we, as partners, imported all construction material from Nairobi and Lokichoggio and catered for all the construction cost.

“But just a month after everything was complete, the lawyer woke up one morning and said he was pulling out of the partnership. We lost over $300,000 worth of investments,” he recounts.

Jackona says their attempts to seek legal redress were futile as the lawyer was working in cahoots with local advocates and the police, posing serious threats to their lives as foreigners.

“So many Kenyans have been arrested, humiliated and intimidated at the behest of their local investment partners. Once released, most have no option but to come back to Kenya empty-handed. It is sad because we treat them so well here,” he charges, revealing that his three colleagues also returned back home.

Jackona says the hostility directed at foreigners, particularly Kenyans, is at times unbearable. He gives examples of Kenyans who have narrowly escaped lynching or paid fines despite being offended in diverse incidents.

“Personally, a drunk military officer rammed into my car from behind near Juba airport in 2010, knocking me off the road. Despite being totally in the wrong, he came out fuming that I had damaged his car and that the accident would never have happened if I were not in Sudan. His colleagues actually insisted that I pay him. But they later left and I had to repair my damaged car,” he narrates.

He says most police officers, as self-appointed arbiters, normally add salt to injury in case of a dispute.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

“In any accident or altercation in South Sudan, it never matters whether you are right or wrong. If you are lucky not to be lynched, you have to pay for damages and be prepared to bribe the police for your freedom,” he claims, noting that the Kenyan Government rarely supports those in trouble.

For Purity Njambi, the pain of doing business in South Sudan is all too clear. Her late husband Dr Joseph Matu was buried in Nyeri last Tuesday after being reportedly tortured and killed by policemen at Torit National Security Station in Juba earlier this month.

Despite claims that he had no license to operate a pharmaceutical, Njambi says this was not the case as they had complied with all regulations. A license issued by the South Sudan Ministry of Health, which was to expire next December, confirms that Matu was indeed operating the business legally.

Post-mortem results

The widow charges that even if the law could have been breached, nothing justifies torturing her husband to death.

“He was ordered to close the clinic and did so but was arrested when he went back to collect his keys. The next time I saw him; he was in a coma in hospital with one tooth knocked off, bruised knees and with a large swelling and cut on the head. His clothes were muddy and he had whiplash marks on the back,” she recounts. Post-mortem results show that Matu, 54, died after being hit with a heavy blunt object in the head.

Njambi reveals that they were planning to relocate their pharmacy and hardware to Kenya next year as hostility intensified.

“For the six years that we have operated in South Sudan, we have been subjected to untold insults and pestering. The locals normally call us thieves and insist that we go back home,” she notes, accusing the Kenyan Government of failing to protect its citizens abroad.

Ruth Wacuka, who has invested in South Sudan over the past six years, says most South Sudan citizens are surviving on money extorted from foreigners. In incidents she describes as routine, she recounts how she lost Sh230,000 to corrupt officers in August last year.

“I had sent one of my staff to withdraw 9,000 Sudanese pounds from a bank in Juba, change it at the Nile Commercial Bank and come back to the office. Some intelligence officers who were trailing him later came in and claimed he was in possession of fake currencies,” she explains.

Wacuka says they arrested the worker and went with the cash. But she notes that despite being cleared of any wrongdoing moments later, the officers released the worker but remained with the cash and a chequebook. “I reported the case to the Kenyan Embassy but they did not even respond,” she states.

Phoebe Omondi, who worked with an NGO in South Sudan for two years, is among the few who are lucky to lead a comfortable life across the border. She says that while her employer provided her with proper housing, transport and round the clock security, agony characterises the lives of most Kenyans who are out on their own.

“The locals believe Kenyans are encroaching on their territory. You even have people who are totally unqualified insisting that they should be considered first when it comes to job recruitment. There is real fear that foreigners are taking their jobs,” notes Omondi.

She terms it scary that most civilians still possess firearms, with the Government yet to conduct a proper disarmament programme since the war ended.

“Some states such as Upper Nile and other oil-rich states are almost no go zones. There is real xenophobia,” she asserts, noting that there is no much room for Kenyans to resist harassment as they lack Government support.

She advises Kenyans to first establish relations, have enough funds to cater for emergencies, be assured of their accommodation and safety before investing in South Sudan.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.