It will be judicial misconduct for a judge to be kicked out of a professional body or even get entangled in private affairs that do not promote public confidence.

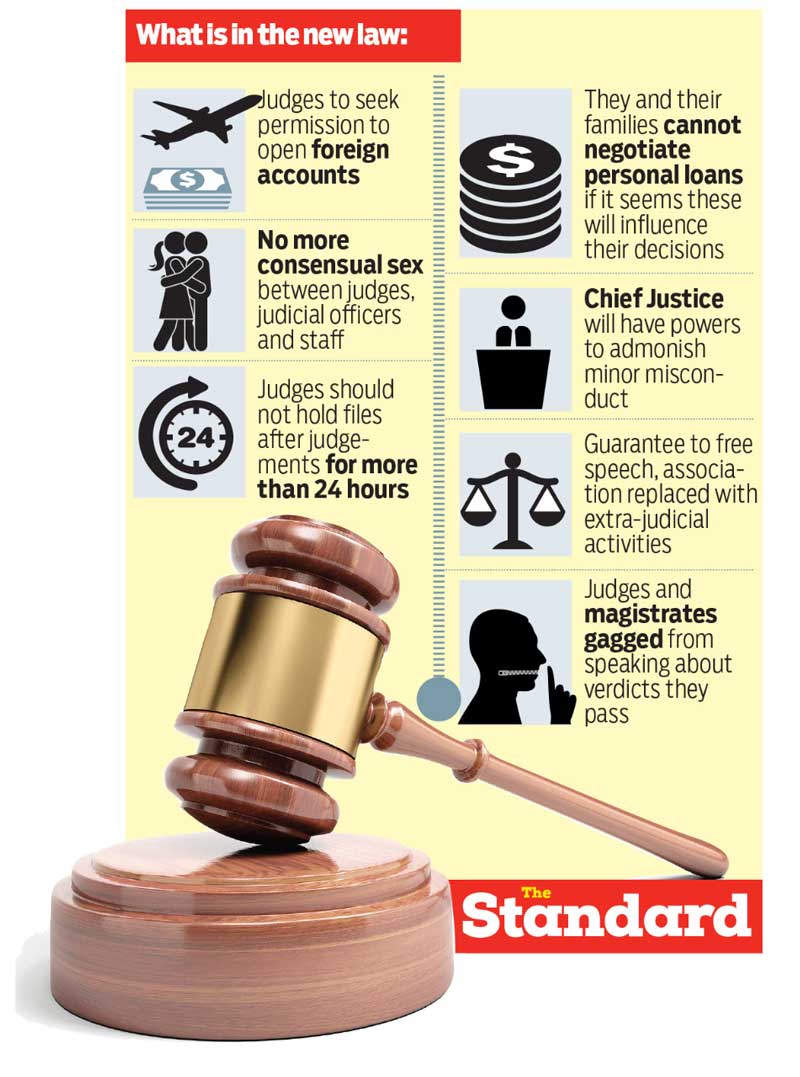

At the same time, judges will have to cautiously seek personal loans since in the event the same is perceived to compromise his or her office, an aggrieved person may seek their removal.

The new law handed by Judicial Service Commission (JSC) to Parliament and exclusively obtained by The Standard has a raft of new conditions, and which are believed will instil public confidence in the Judiciary and how judges, magistrates and kadhis handle cases.

Although the Constitution provides that a judge should be removed from office for judicial misconduct, even a minor one, the regulation has settled the long-standing battle on whether a Chief Justice can discipline or admonish a judge for minor misconduct by prescribing it under the disciplinary procedure.

“Without derogating from the provisions of Articles 168 and 172 of the Constitution, breaches of this Code that amount to minor infractions and administrative lapses by judges and judicial officers shall be dealt with by the Chief Justice as the administrative head of the Judiciary,” the 2020 law reads in part.

JSC had a long-standing battle with some Supreme Court judges on whether a Chief Justice has powers to admonish a judge. Judges maintained he has no such powers, while JSC argued that not all misbehaviour qualifies for the removal of a judge.

In the new law, it will be illegal for judicial officers to misuse information in their possession.

In the 2016 law, the issue of loans appeared once — on a section of accountability and prohibition against corrupt practices.

However, in the proposed law, it appears four times indicating it is a teething issue in the Judiciary.

The word first appears under a section dealing with integrity, and here, judges are personally barred from accepting any gifts, personal loans, bequests, benefits or any other things of value, if acceptance is prohibited by law and would compromise his or her integrity.

It then appears thrice, under accountability and prohibition against bribery and other corrupt practices.

In the first part, a judge or magistrate is punishable by sacking if a personal loan is perceived to have compromised his duties.

It will also be illegal for judges’ families to directly or indirectly negotiate or accept gifts, loans, remunerations or benefits which are incompatible with judicial office, and which can be perceived as being intended to influence them.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

The 2020 law has spelt the end of consensual sex between judges, judicial officers and staff.

In the 2016 code, there was a caveat which provided consensual sexual behaviour that is based on mutual attraction and did not constitute sexual harassment.

In the new one, that clause is missing.

Judges will also be required to seek permission from the Chief Registrar of the Judiciary to open bank accounts outside Kenya and those currently holding such accounts will be required to give unfettered access to their employer for scrutiny.

“A judge who operates or controls the operation of a bank account outside Kenya shall submit statements of the account annually to the Commission, and shall authorise the Commission to verify the statements, and any other relevant information from the foreign financial institution in which the account is held,” the regulations handed to Parliament on September 11, 2020, read in part.

However, an outcry is emerging that judges and magistrates were allegedly not involved while JSC was drafting the new law. Those who spoke on condition of anonymity claim the new code of conduct is too intrusive.

“We had a perfect 2016 law but this one… They have now roped in our private lives; the accounts issue and even loans is too much. I am sure other officers do not know if this exists,” an officer said, adding “I believe some of those regulations are targeting individuals.”

The code of conduct also forbids a judge or a magistrate or a kadhi from holding back a case file for more than 24 hours after delivering judgements.

JSC has done away with a previous section which guaranteed judges and judicial officers were entitled to freedom of expression, belief, association and assembly so long as they maintained the dignity of the judicial office and the impartiality and independence of the Judiciary.

Instead, the new law reads that a judge or a judicial officer may participate in extra-judicial activities associated with his rights of citizenship unless such activities touch on his or her partiality and are likely to affect his or her time to carry out judicial duties.

It has, however, gagged them from speaking to a litigant or any other person relating to even cases which have already been determined. It is presumed that judges should only speak through their judgements.

It has also left judges and judicial officers to run personal social media accounts.

And judges in the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court will no longer personally withdraw from benches constituted from hearing cases, instead, the entire bench will decide the fate of one of their own.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.