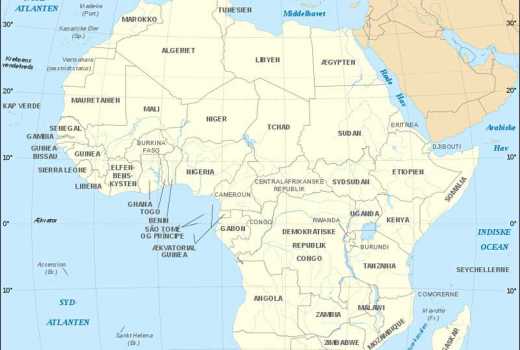

Our Pan-Africanist ancestors just sat up and took notice. I have often imagined that most days our ancestors look down at us and shake their heads in disbelief as African Governments squander and mismanage natural resources and public taxes. Those cynical thoughts were punctured for a moment on March 21 when African Governments met in Kigali to discuss and sign three policy instruments that create a single African trade market. The three instruments establish an African Continental Free Trade Area and the right of Africans to move, work, invest and reside anywhere in the continent. Forty four states supported the move to a common market and 22 states signed the free movement instrument. Alongside 27 Heads of States, Uhuru Kenyatta signed all three instruments.

With a collective population of over 1.2 billion people and GDP of US$2.6 trillion, this is the biggest trade area since the World Trade Organisation was established. Africa is on the verge of a GDP equivalent to Britain or four times the size of Malaysia, Mexico or Brazil. The move strikes a blow to the difficulties facing small-scale traders and large companies trading across Africa. Up to now, trade tariffs and taxes on imports from other African countries has averaged 6 per cent and 52 per cent. This has made trading among ourselves too costly. The moment has been long in coming.