×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

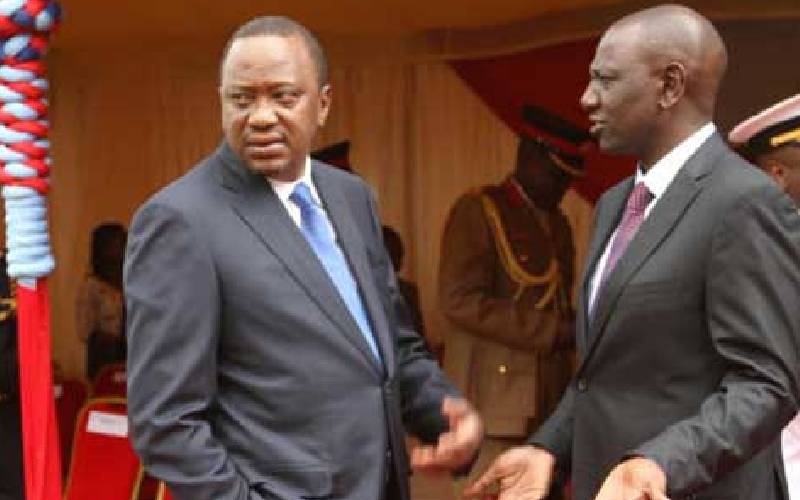

President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto.

“You are going to have lunch with the President. The menu is humble pie. You’re going to eat every last spoonful of it. You’re going to be the most contrite sonofabitch this world has ever seen,” James A. Baker III