×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

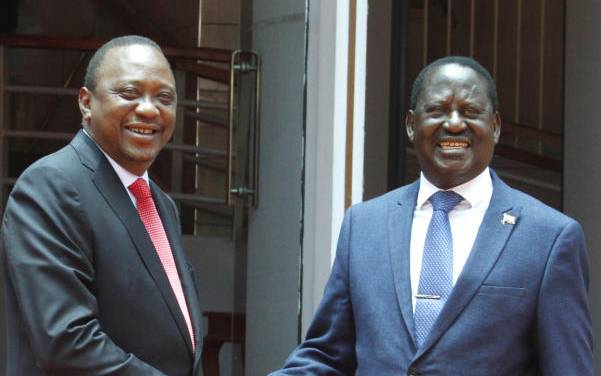

President Uhuru Kenyatta and ODM leader Raila Odinga shake hands after they reconciled in the famous handshake following the bitterly contested August 2017 Presidential Election. [File, Standard]

Vote-rich Mt Kenya bloc, which for the first time since 1992 looks set to be without a serious presidential contender, has been flipped into a battleground region that could swing the 2022 presidential race.