×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

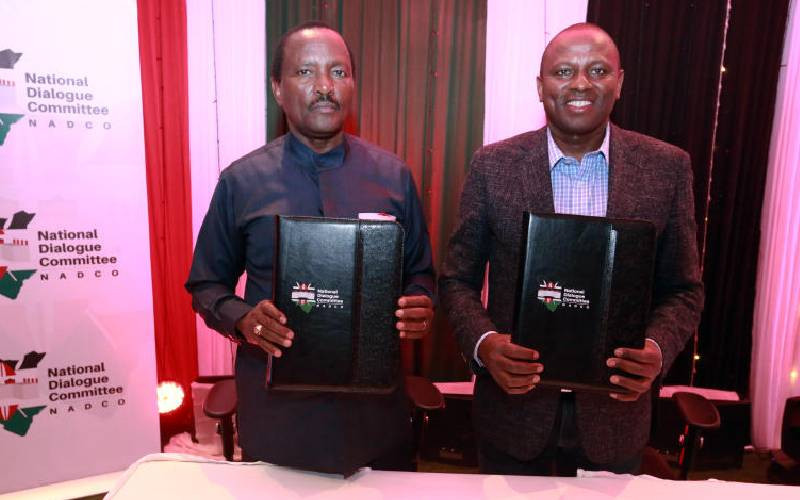

A critical task facing the 13th Parliament is the examination of the National Dialogue Committee (NADCO) Report, much like how its predecessor, the 12th Parliament, handled the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI).

The inception of the NADCO process followed Azimio-led mass demonstrations after the coalition's 2022 presidential ballot challenge. Hence the establishment of a committee with the mandate to facilitate dialogue, consensus-building, and recommend electoral, governance and socio-economic reforms.