×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

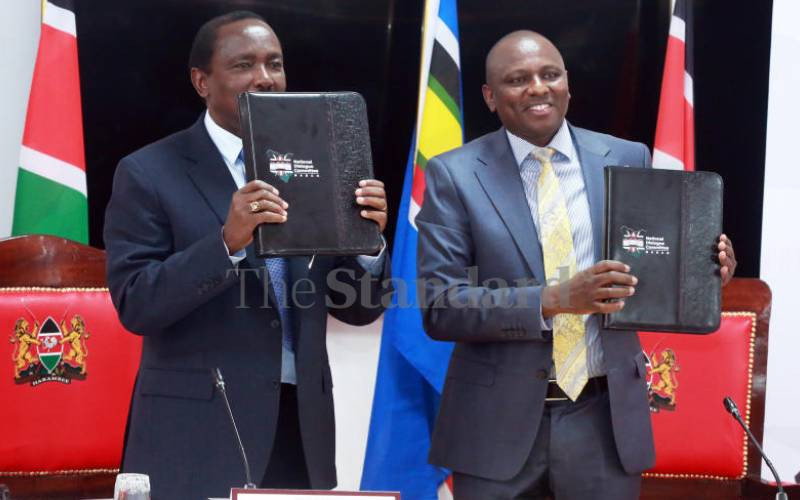

We return to the report of the National Dialogue Committee (Nadco). But first, here is a test.

As the New Year approached, two unrelated "data events" happened in Kenya. The first was Tifa's publication of its year-end opinion poll on Kenyans' reflections of 2023. The second was the latest data release on inflation by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS).