×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

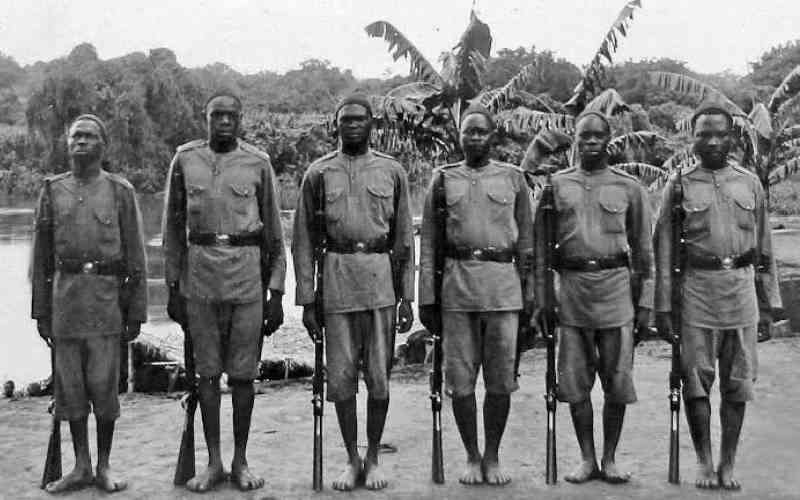

Although the exact year when the police embraced uniform is not clear, the search for the 'ideal' attire continues 121 years later.

Since 1902 when police was established, evidence of a force/service struggling to come up with the right uniform is littered along the way.