×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

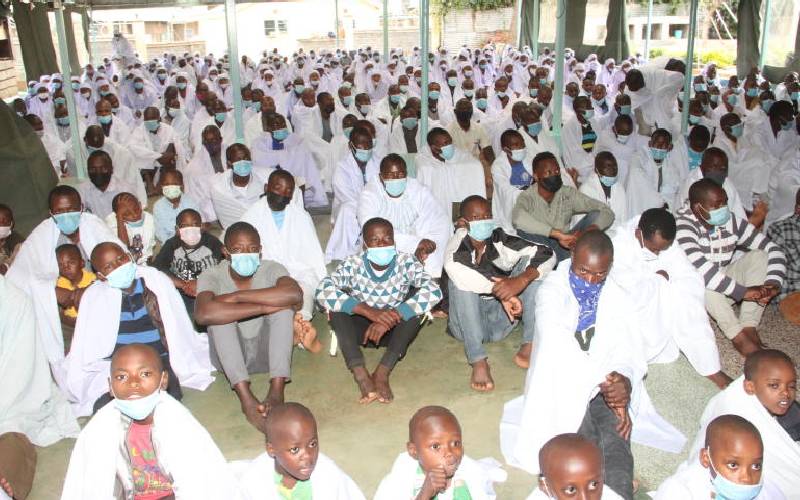

A group of Shona community whose origin is from Zimbabwe at their church Gospel of God Church located at the junction of Valley Road and Ngong Road.[Edward Kiplimo,Standard]

Kefasi Murwira Marufu, 78, has never had a bank account or a phone in his name.