×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

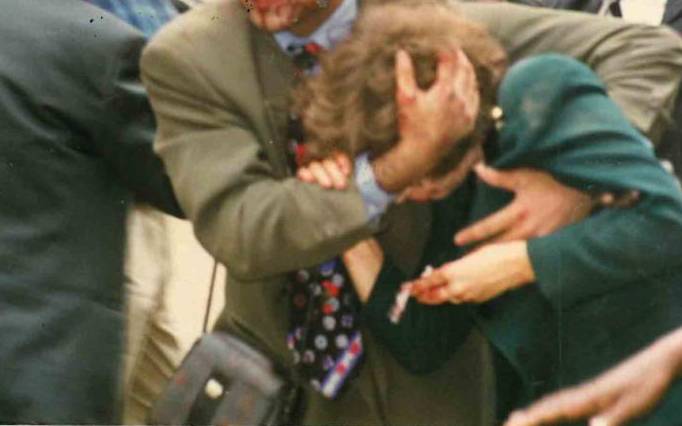

Meet Prudence Bushnell, the American ambassador to Kenya when the 1998 Nairobi bomb attack happened. Quick –witted, reflective and intense, she shares with JUDITH MWOBOBIA what she has been up to, her reflections of that fateful day and lessons life has taught her.

Twenty-one years ago, in Nairobi, on a seemingly beautiful day in August, Ambassador Prudence Bushnell, left her residence to go to work. She had an important meeting with the then Trade Minister Joseph Kamotho.