×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

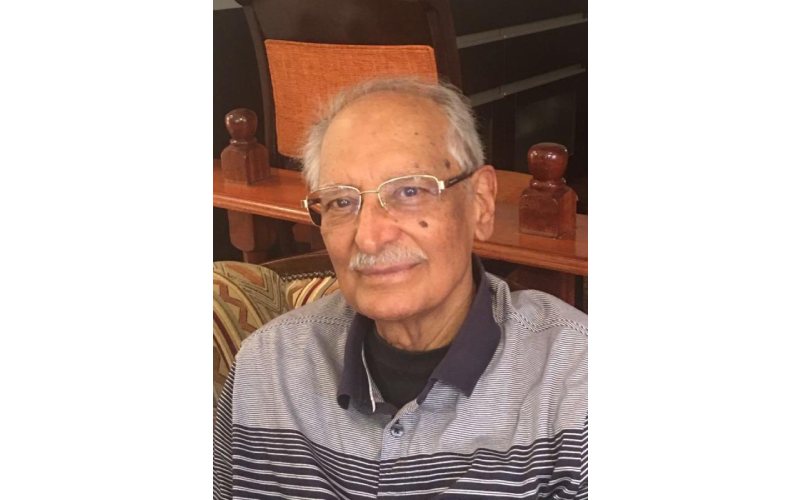

Only a certain generation of Kenyans know Bhushan Vidyarthi. And after hearing news of his death on Thursday, this select group of people were swept with sadness. Politicians, publishers, businessmen, government officials and activists all united in grief.

But a look at Bhushan’s life indicates that their grief was justified for his and his family’s history in Kenya demands more than a shrug of the shoulder and an acceptance that life must indeed go on.