×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

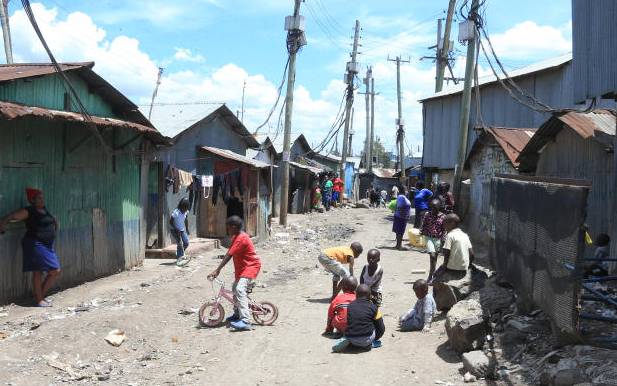

Children play in the Mukuru Kwa Reuben slum in Nairobi, Kenya, where life seemed to be normal for the residents. They were not wearing masks and observing social distances as required by the government to prevent the spread of coronavirus. Most slum dwellers cannot afford personal protective equipment such as masks and hand sanitisers. [Stafford Ondego, Standard

Having ravaged some of the world’s wealthiest cities, the coronavirus pandemic is now spreading into the megacities of developing countries.