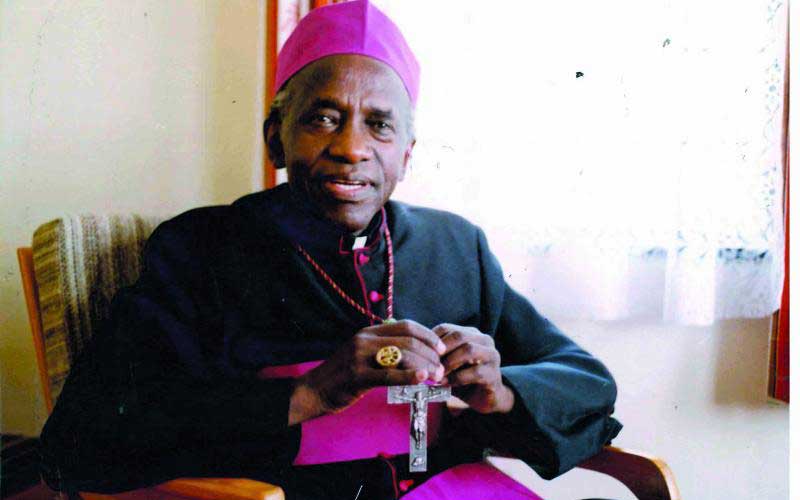

Most people knew him as a man who stood up to power. But what they probably do not know is that he was a fierce defender of the African spirit and the African contribution to the Catholic liturgy.

After every five years, the bishops of the Catholic Church all over the world are obligated to pay a visit to the Vatican. This is called the Quinquennial ad limina visit to Rome. It is an ancient custom and Church Law that decrees that every bishop who heads a diocese must go to Rome to make a pilgrimage known as ad limina apostolorum (To the thresholds of the apostles).