×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

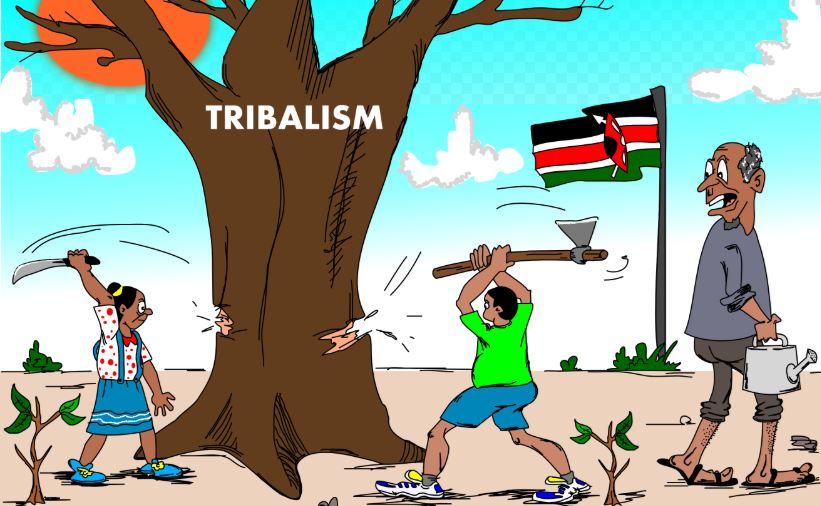

Leaders who divide their people never understand what peace means to the ordinary Nandi or Luo. It means everything.

Because such leaders reside in high places where they will live eternally, they never realise that the absence of inter-communal peace disrupts people’s lives forever. As I wrote in the past about my little village in Songhor, Muhoroni, education ended for children of the late Mzee Carillus Odoro (claimed by the border clashes of 1992).