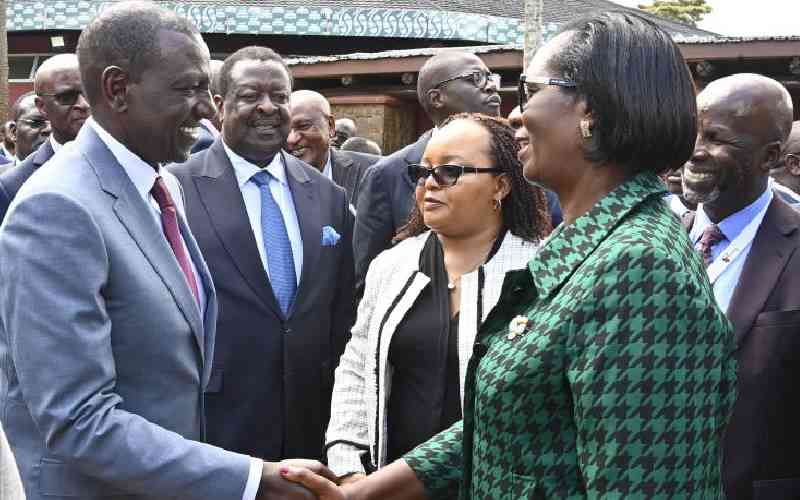

- Dignitaries arrive at KICC for day 2 of the Africa Climate Change Summit

- Global Hunger Index 2022: Rebuilding food security on a lasting basis - part two

- Global Hunger Index 2022: Rebuilding food security on a lasting basis - part one

- How climate change, politics, and resource competition collide in Kenya's fertile Laikipia plateau

- Farmers in some parts of the country harvest food crops even as millions face starvation

×

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print operations, television, radio broadcasting,

digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a leading

multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print operations, television, radio broadcasting,

digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a leading

multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print operations, television, radio broadcasting,

digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a leading

multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a multi-media organization with investments in media

platforms spanning newspaper print operations, television, radio broadcasting,

digital and online services. The Standard Group is recognized as a leading

multi-media house in Kenya with a key influence in matters of national and

international interest.

- Standard Group Plc HQ Office,

- The Standard Group Center,Mombasa Road.

- P.O Box 30080-00100,Nairobi, Kenya.

- Telephone number: 0203222111, 0719012111

- Email: [email protected]

NEWS & CURRENT AFFAIRS

TV STATIONS

RADIO STATIONS

ENTERPRISE