Audio By Vocalize

Joint Response by the Nominated Oil Marketing Companies on the Statement by Raila Odinga on the Government-to-Government Fuel Import and Supply Framework

Background

For almost two decades, Kenya imported its petroleum fuels under the monthly Open Tender System ("OTS") through which the oil marketing companies aggregated their requirements, and a tender coordinated by the ministry responsible for petroleum called and awarded the most competitive bid to import a cargo (or cargoes) of the specific grade of fuel it tendered for.

The bid element for fuel supply has traditionally been and remains the Freight and Premium (F&P) component. Freight is the cost of chartering and delivering a ship from the port of loading to the discharge port. Premium is a charge that accounts for the refinery margin, load port related expenses and the international oil supplier's margin.

The OTS required the buyers to pay for the fuel products promptly upon discharge of the vessel, and certainly not later than 5 days from ship completing discharge; with attendant penalties for failing to do so. Payment currency was United States Dollars.

Towards the end of 2021, as the US Federal Reserve began raising interest rates on US Treasury Bills, most emerging markets started to experience challenges obtaining adequate supply of dollars to meet their obligations. In Kenya and the region, the challenge experienced by OMCs manifested itself in delays in payment for fuel products. This progressively worsened into early 2022, leading to sporadic stockout of fuel across many retail outlets.

Legal Notice 44/2008 requires OMCs to maintain 20 days stock cover so as to assure security of supply. For the better part of 2022, most OMCs were unable to maintain more than a few days of stock holding due to the debilitating dollar shortages. Further, the banks financing OTS cargoes were growing weary of the risk of non-payment, with LC maturities frequently occurring before payment for the fuel by OMCs, which was in contravention of the OTS Tender Terms and Conditions.

Given the requirement for prompt payment for fuel in dollars, a situation emerged where all the OMCs were chasing very scarce dollars, creating a speculative bubble in the forex markets.

At the behest of OMCs to provide a lasting solution to the forex challenges, and against the backdrop of other competing priorities, the Government of Kenya sought a mechanism to reduce the pressure on dollar liquidity not only for the oil sector, but the wider economy. This necessitated a review of the import system to allow for deferred payment terms, provide for oil marketers to pay for fuel in Kenya Shillings and facilitate an orderly approach to forex markets closer to maturities of the longer tenor Letters of Credits (LCs), thereby eliminating the dual risk of stock-out and forex speculation.

Specific responses to the questions raised are answered here below:

A1. Purchasing fuel in Kenya shillings is a lie.

R1. Under the G-to-G framework, the local OMCs pay for petroleum in Kenya Shillings ("KES") and are no longer required to source for dollars in the local market. Previously OMCs were each required to source for dollars thereby creating artificially heightened demand which would cause distortion in the Forex market and echo to the rest of the economy.

G-to-G provides a structured approach for the purchase of dollars in the local market thus bringing stability to the KES.

A2. There was no G-to-G. Kenya did not sign any contract with Saudi Arabia or the UAE. Only the Ministry of Energy and Petroleum signed a deal with state-owned petroleum companies in the Middle East.

R2. This is not true. There is an MoU between the Government of Kenya and the governments of the IOCs, also supported by long-existing bilateral trade relations between Kenya and these countries.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

A3. G-to-G was meant to shield the three Kenyan companies from paying 30 per cent corporate tax.

R3. This is categorically not true. There is no exemption from payment of any tax (no tax exemption has been sought by the nominated OMCs, nor has the GoK offered any). The Kenyan companies involved in the G-to-G supply pay their corporate taxes, and all other taxes like any other organization. It is a requirement under the Energy Act 2019 and Petroleum Act 2019 that an Oil Marketing Company must obtain a Tax Clearance Certificate in order to be issued with or to renew its Import Wholesale and Export Licence for Petroleum Products. A valid Import, Wholesale and Export Licence is a pre-requisite for a company to be a seller of product under the OTS Agreement or the G-to-G Agreement.

The tax compliance status of the Nominated Oil Marketing Companies is easily verifiable through the Kenya Revenue Authority.

A4. The cost of oil has not come down since the deal was signed.

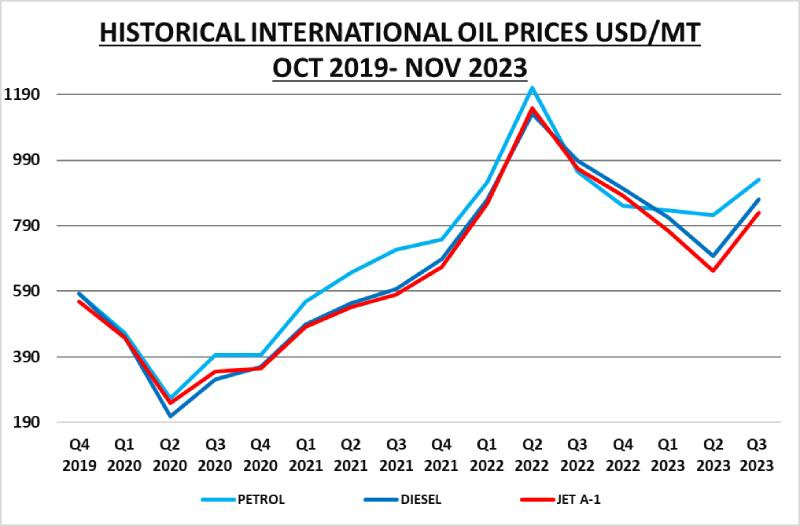

R4. The local cost of fuel is determined by international oil prices, the prevailing forex rate and applicable taxes. Please see chart below that shows global oil prices have been steadily rising due to the global post-COVID recovery in demand, and certainly more with the geopolitical challenges over the last 18 months. It is noteworthy that the world prices have been rising from Quarter 2 of 2023 which coincided with the start of the G-to-G supply.

A5. The shilling has continued to fall against the dollar.

R5. The depreciation of the KES against the US dollar is a result of the macroeconomic factors not specific to the oil sector including the global strengthening of the dollar and the Federal Reserve Bank of the United States raising rates; this is not a purely Kenyan phenomenon.

It is instructive to note that the depreciation rate of the Kenya shilling rate would have been much higher were it not for the intervention created by the G-to-G by deferring the demand for dollars by OMCs from the forex spot markets.

A6. The scarcity of the dollar has continued.

R6. As above.

A7. The landlocked countries that depend on us for oil are abandoning our pipeline because it has become too expensive.

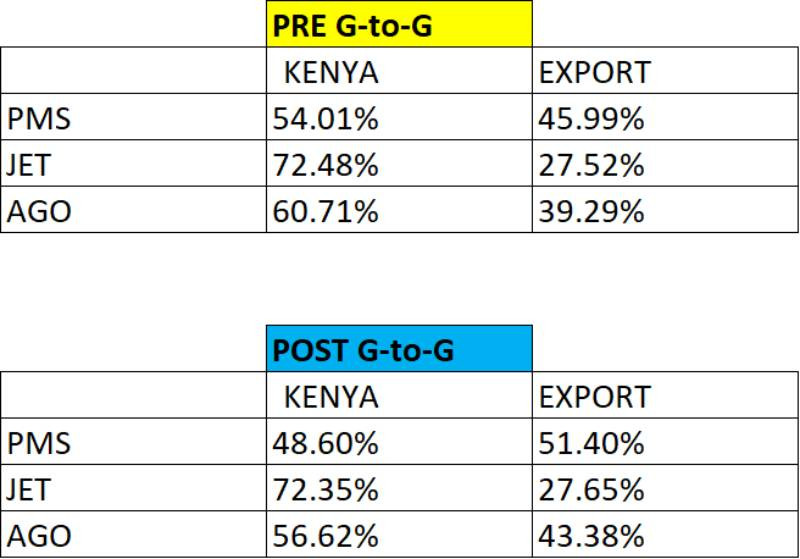

R7. This is not correct. Publicly available data shows that the volume of fuel transited to the land-locked markets has actually increased under the G-to-G compared to the previous importation system. This data is an endorsement of the Northern Corridor as a preferred route by the transit markets. Please see Table 2 below showing Kenya vs export volumes before and after G-to-G.

Table 2

A8. The US-dollar to Kenya-shilling exchange rate was Ksh132. Today, six months later, it is Ksh159 to the dollar

R8. As indicated in R5 above, this depreciation would have been worse were it not for the intervention of G-to-G. It is a fact that during the period of scarcity of forex prior to the G-to-G implementation, there existed a parallel market that was selling dollars at rates much higher than the rate published by the Central Bank.

A9. The cost of fuel shot up significantly after the deal.

R9. As indicated in R4 above, the price of fuel is largely determined by international oil prices and prevailing exchange rates both of which have-been on an upward trend long before the inception of G-to-G.

A10. Other than keeping the cost of oil permanently high in Kenya, the deal is costing the country dearly in terms trade in petroleum with landlocked neighbours.

R10. This, again, is not correct. As per Table 2 above, which shows Kenya vs export volumes before and after G-to-G, the export volumes to landlocked countries have increased since the inception of G-to-G framework.

A11. It is shrouded in deep secrecy. To date, only two documents have been made public; that is the Master Framework Agreement with petroleum trading entities and the Open Tender System modified agreement with marketers.

R11. On the contrary, the whole process has been transparent. The Master Framework Agreement ("MFA") and all other documents pertinent to the G-to-G process have been presented to the Select Committees of the National Assembly and the Senate. In addition to this, all Oil Marketing Companies are intimately familiar with the documentation pertinent to the G-to-G transactions including all shipment details on a vessel by vessel basis.

Prior to operationalizing the G-to-G Framework, the Ministry of Energy and Petroleum actively engaged the stakeholders including the OMCs, international suppliers and financial institutions participating in the fuel supply and financing in Kenya, to come up with a structure that addressed all stakeholder requirements and at the same time assuring the country of reliable supply of petroleum products.

A12. The Supplier Purchase Agreement between the Middle East Oil firms and their hand-picked distributors in Kenya has never been seen.

R12. These are counter-party agreements dealing with shipping of products, vessel planning and custody transfer of products.; they have no bearing on the price of fuel; they cover terms and conditions of how the local OMCs will operationalize the MFA. The price charged to the consumer is clearly set out in the MFA.

The nominated OMC cannot charge anything outside of what is set out in the MFA and the OTS price build-up structure. The G-to-G transactions have maintained the OTS pricing structure and practices and norms which are well understood.

A13. Nobody knows how Gulf Energy, Galana Oil Kenya Ltd and Oryx Energies Kenya Limited got nominated to handle local logistics

R13. Noting that the main task of the nominated OMCs is to operationalize the Master Framework Agreement and their nomination has no bearing on the final price payable by the consumer, their nomination was the exclusive prerogative of the IOCs and was purely based on performance in delivering fuel into the country under the previous OTS System.

The Government had no role in nomination of the three OMCs. The international oil companies nominated OMCs who they independently determined had a clear track record of importing and distributing fuel to the industry, past trading relationships with the IOCs, and capacity to handle transactions of this nature.

Prior to G-to-G, the three nominated OMCs delivered over 67% of cargoes under OTS due to consistently bidding the lowest prices. They thus have a proven track record of importing and distributing oil to other OMCs and the region prior to G-to-G.

A14. The hand-picked Distributors are selling oil to us at almost twice the price from bulk suppliers

R14. This is not correct. There was no 'hand picking' by Government. Further, fuel is not being sold at 'almost twice the price from the bulk suppliers'.

The Government had no role in nomination of the three OMCs. The international oil companies nominated local OMCs who they found had a clear track record of importing and distributing fuel to the industry. The nominated oil companies discharge and supply the imported fuel to the other oil marketing companies at the same price negotiated by the government in the Master Framework Agreement.

The nominated OMCs are not allowed and do not add any mark up on the contractual freight and premium in the MFA.

A15. These companies are also manipulating delivery date ranges so that they can maximize on prices.

R15. This is not correct at all.

A nominated OMC is not allowed and cannot change the price based on change in delivery date ranges. As per the Master Framework Agreement, the nomination of delivery dates is done by the entire oil industry based on demand forecast and delivery dates issued by the Ministry directly to the international oil companies.

A16. The government allowed Oryx Energies to sell oil at prices that had been inflated by 17 percent In the deal, Oryx is the supplier of diesel to other oil marketing companies (OMCs) in the country. The excuse was the delay in discharging fuel at the jetty.

R16. As above, this is also not correct.

This specific cargo (KGV14/2023) was nominated for delivery in August by Ministry of Energy vide letter to the IOC concerned, with pricing month clearly indicated as July 2023.

The cargo was delivered on 19th August 2023. The oil marketers were billed and they subsequently paid based on July pricing per as the nomination letter.

This can be confirmed from EPRA prices announced on September 14th, which covered all cargoes discharged between 10th August to 9th September 2023. This is a publicly available document from EPRA website.

Please see R18 below in further explanation.

A17. They buy at low prices, delay in discharging, then ask to be allowed to offload at higher prices and the cost is passed to consumers.

R17. This is simply not correct. As indicated above, price does not change on the discharge date. The planning of supply and pricing is undertaken 2 months in advance by Ministry of Energy and the Supplycor (other OMCs). The Nominated OMCs have no role in determining these dates; they only supply and invoice as per the date range provided by Supplycor (supply coordinator on behalf of OMCs).

A18. In the case of Oryx, it had bought the diesel at an average Platts price of $97.88 (Sh14,182) per barrel in July, but was allowed to sell the same to OMCs at $114.5 (Sh16,585) per barrel.

R18. This is simply not correct. Oryx obtained the cargo at the mean of Platts of $97.88 per barrel and sold at $97.88 per barrel to other OMCs and not the alleged $114.5. This simple fact can be confirmed from any registered OMC in Kenya and from EPRA. As previously stated, the nominated OMCs can only distribute the imported fuel at the price obtained at the G-to-G negotiated prices (i.e. the Platts price).

This is easily verifiable from EPRA.

A19. Some of the companies charging the higher prices deliver more cargo than they were contracted to deliver, forcing Kenyans to buy more of the oil whose prices are inflated, hence the permanent high prices of petroleum products.

R19. This is deliberately misleading. The Master Framework Agreement has locked in the monthly quantities to be imported. As is the norm in oil trading, the Master Framework Agreement allows a tolerance of +/-10%.

Under no circumstances are the nominated OMCs clandestinely delivering more cargo than the contractual quantities.

Critically, all oil is paid for at the rate in the G-to-G Master Framework Agreement and there is no 'inflation of prices'.

A20. The Ministry is changing billing month to allow the oil firms quote higher prices.

R20. This is simply not correct. Two months in advance of delivery, the Ministry nominates quantity and delivery dates which forms the basis of pricing. The prices are therefore in the future and this eliminates the possibility of speculation of price or mischief.

Billing procedures are strictly enforced as per the Master Framework Agreement and the OTS Tender Terms and Conditions. Further, as stated above, the price does not change on the discharge date.

A21. For instance, cargo that was bought in July when the price was low is allowed to quote higher August prices and pass the burden to the consumer.

R12. Statement is simply untrue; please see R20 above. Cargo bought internationally in July was invoiced to the local market based on the same pricing terms.

A22. The deal has resulted in high landed cost as a result of the structuring of the contract. The faults include the double counting of some cost elements and fixed freighted premium which sometimes are higher by up to $50 per metric tonne. The cost is passed to consumers.

R22. This is also untrue.

There is no 'double counting' in cost elements. The structured contract for Kenyan supply is beneficial to the Kenyan economy in that it extended the payment period provided by international oil companies from 30 to 180 days thereby stabilizing the KES against the USD and availing the dollars for the rest of the economy whilst ensuring security of supply of fuel.

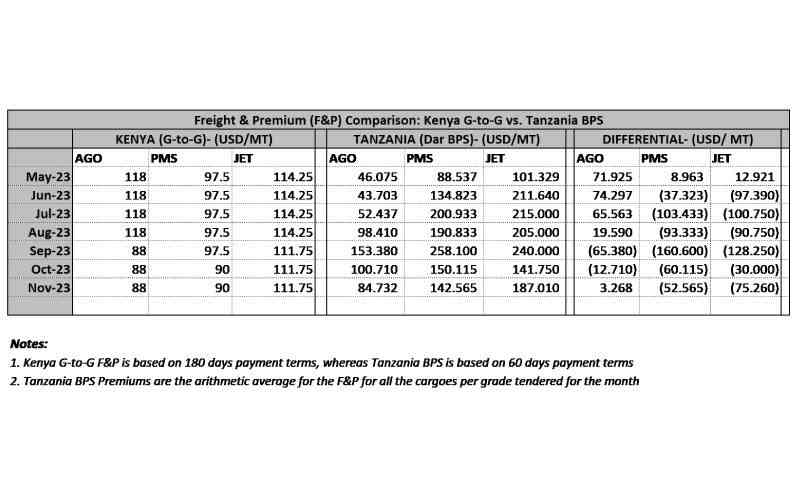

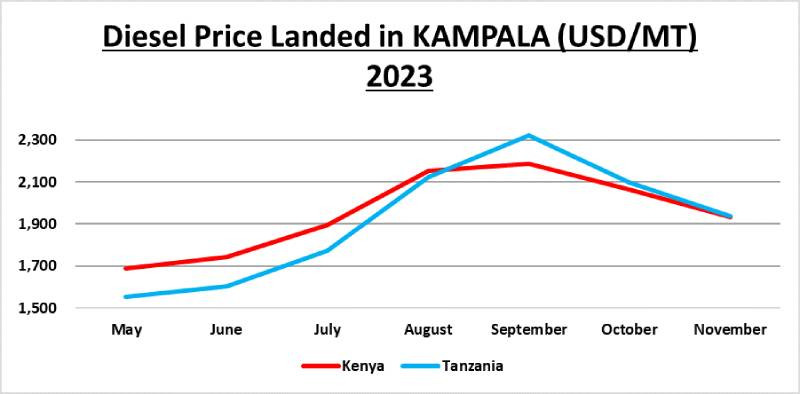

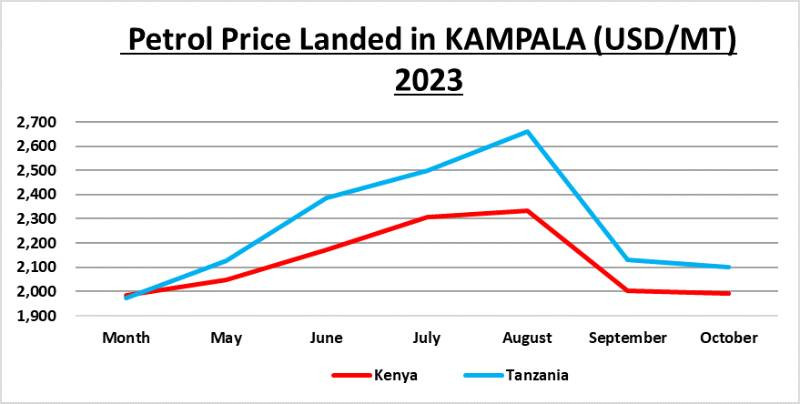

Please see Table 3 showing a comparison of freight and premium between Kenya and Tanzania for the G-to-G period.

Table 3:

A23. It also lacks flexibility which further exacerbates the pricing model.

R23. The fixed premium contract cushions the country against spikes in international freight and premiums as witnessed in the month of September to November 2023 in the Tanzania imports via Tanzania's Bulk Procurement System (BPS).

A24. Uganda has announced it would no longer purchase petroleum products from Kenya because middlemen have inflated prices by up to 59 per cent, imposing too high a cost on consumers. The exact same scenario is prevailing here.

R24. This is not correct; the Master Framework Agreement creates a direct engagement between international oil companies who are amongst the largest producers and refiners of fuel in the world, the oil industry in Kenya and the Government of Kenya.

There are no 'middlemen'.

A review of the freights and premiums as indicated in Table 3 above shows that Kenya continues to enjoy competitive freight and premiums compared to Tanzania notwithstanding the extended credit period for Kenya.

A25. The deal has interrupted supply. This is because the single bank that was picked to provide the LC is struggling with big bad loans. Consequently, there is delay for clearance of importers to offload oil.

R25. On the contrary, there has been no supply shortage since the G-to-G transactions began. The deferred payment terms under the G-to-G contract is 180 days from Bill of Lading Date. The first deliveries started in April 2023 and the first LCs were to be settled towards end of September 2023. Utilization of bank facilities by the nominated OMCs was expected to peak in September / October 2023. Towards the end of September and early October, the first LCs matured and were paid. Payment of LCs takes place as each falls due.

To note, there are more than 5 banks financing the process and not a 'single' bank. Several others are in the process of onboarding to finance the supply of fuel under the G-to-G structure.

It is instructive to note that all funds for cargoes are paid prior to release of product, and invested in the Escrow accounts awaiting maturity of the LCs to settle the obligations. All cargoes are fully funded. Further, there are no bad loans. All the cargoes financed to date have been paid in full to the financing banks and the banks await the maturity date of the LCs to settle the international suppliers.

A26. Ships are queuing at sea for up to 18 days awaiting confirmation of LC in order to discharge while the Kenya Pipeline Company goes without operations for days because there is nothing to process. Then the companies incur demurrage, which is transferred to the consumer. Under the Open Tender System, demurrage costs are $45,000 per day for the biggest tanker (LR2) docking at the Port of Mombasa and $31,000 per day for the second-biggest vessel (LR1).

R26. The issue of occasional queuing of the vessels awaiting discharge is common in most ports in the world. The delays alleged in the month of October are not unique. It is important to note that heavy rains in most of East Africa has temporarily impacted movement within South Sudan, DR Congo, Uganda and parts of Kenya, leading to lower uptake of fuels especially of diesel. The vessels currently waiting to discharge have fully issued and confirmed LCs.

Demurrage rates are driven by various global shipping dynamics and it is common to have spikes of demurrage rates due to geopolitics like war and pandemics.

A27. You will have noticed that Tanzania recently reduced the cost of petroleum products from 1 November while Kenya's remain the same or just marginally changed. Tanzania said it was reducing prices because of decrease in world oil prices by an average 5.68 per cent while premiums for importation of petroleum products had decreased by an average 13 per cent for Super Petrol also known as Premium Motor Gasoline or Premium Motor Spirit (PMS) and 25 percent for Automotive Gas Oil or diesel.

R27. The difference between Tanzania and Kenya pump prices is purely as a result of a difference in pricing month for cargoes going into the price calculation i.e. Tanzania pump prices are based on the international Platts prices for two months prior to the pump price publication date (M-2) whereas Kenya's pump prices are based on the international Platts prices for all cargoes received from the period 10th of the month prior up to the 9th of the pump price publication month (M-1).

The difference between the reference months used by the two countries occasions the differences in published pump prices. It is typical to have prices swinging in favour of or against either country side based on the above explanation.

A28. As ships accumulate extra charges in the seas, the money sits in an Escrow account in a local bank where it earns interest. It remains unclear who the beneficiary of the accrued interest is.

R28. It is a requirement of the G-to-G agreement that funds paid by OMCs are placed in an interest-bearing Escrow Account. The interest earned from the funds in Escrow is applied fully for the benefit of the consumer when costing the product pump price. This is easily ascertainable from EPRA.

A29. This deal has led to high cost of oil products sourced through the Northern Corridor Transit Route (Kenya route).

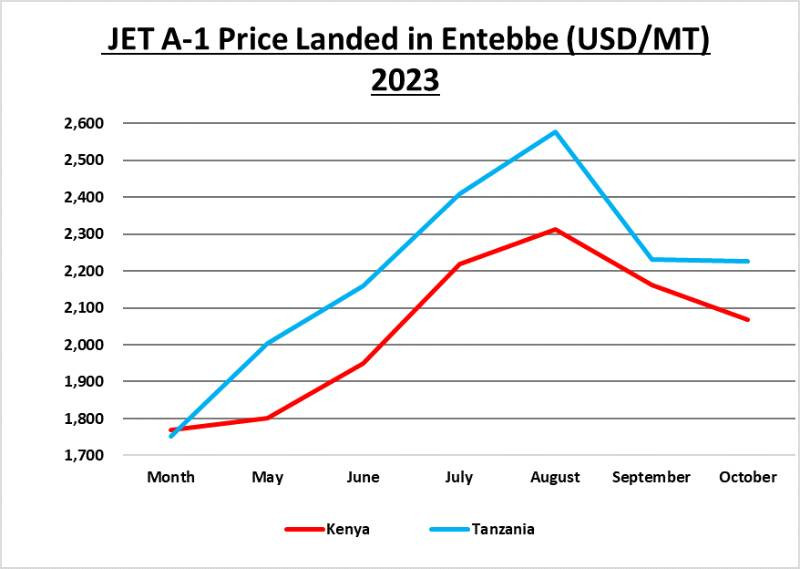

R29. This is not correct, please see charts below which compare the landed cost in Kampala for the various grades of fuel comparing the Kenya corridor vs Tanzanian corridor. A review will show that for the majority of the period, fuel delivered through Kenya G-to-G landed in Kampala more competitively than via the Tanzania BPS.

A30. The freight and premium rates for May 2023 cargoes were higher in the Northern Corridor by 61 per cent compared to the Central Corridor. That rise in freight and premium is reflected at the pump.

R30. A review of the F&P prices for the period April to November 2023 comparing Kenya G-to-G to Tanzania BPS shows clearly that the Kenya G-to-G continues to offer more favourable prices. It is further noteworthy that the Kenya system continues to offer on average lower freight and premiums and 3 times longer credit days.

Basically, the above allegation is not borne by the facts; the Kenya Northern Corridor is objectively more economical than the Central Corridor.

A31. That is what has pushed Uganda and other forward markets like South Sudan, East DRC, Rwanda and Burundi to consider importing goods through the Central Corridor or Tanzania route. Uganda is shifting to the central corridor. The volume it ferries via Kenya Pipeline has dropped to 52 per cent, from 70 per cent. So, other than making petroleum products ever more costly, the deal is going to kill the Kenya Pipeline Company as soon as this year. The transit volumes account for 51 per cent of Kenya Pipeline Company's revenue which stands at an average Kshs. 2.6 billion per month.

R31. Uganda has historically been partially supplied through Tanzania's Central corridor. Rwanda and Burundi are supplied almost exclusively via the same corridor.

As indicated in R7 above and Table 2 above, the transit volume from Kenya to regional export markets has actually increased under G-to-G therefore earning KPC more revenue and higher Forex earning.

A32. When the company loses in the volume transported, it results in higher tariffs which is transferred to the local consumer in terms of higher cost of petroleum products. A 10 per cent reduction in the transit volumes would result in a 5 per cent increase in tariff, which is reflected at the pump in terms of cost of fuel.

R32. As noted in Table 2 above, KPC has not lost any volume.

A33. The change of route by land locked trading partners will force a number of Kenyan Oil Marketing companies and logistics firms to close shop. Of course this leads to job losses, loss of foreign exchange, loss of revenue for the country as a result of KPC losing transit share.

R33. This is not correct. The transit product is usually manifested and consigned directly to companies in the transit markets and Kenyan companies will continue operating as usual. As previously noted, the Kenyan route remains more competitive and the preferred option for transit markets.

A34. Ideally, Kenya should have provided a pipeline and storage capacity allocation for Uganda market. Kenya should also have allowed the direct participation of Uganda oil marketers in sourcing petroleum products through the northern corridor route.

R34. As reported in various media, Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC) applied to EPRA to obtain an import, wholesale and export licence and to join the KPC transport and storage system. This is clear testimony that that Uganda prefers to continue using the Kenyan Northern Corridor for its supplies, and consolidate more volumes through the Kenyan corridor. UNOC's plan to use the KPC system will further consolidate any volumes not presently coming through the Kenyan corridor into KPC further improving the revenues of KPC and driving higher capacity utilization of Mombasa port.

It is instructive to note that Kenya recently commissioned a new deep draught oil jetty, capable of handling multiple vessels; and is presently expanding its storage and pumping capacity to better serve the region.

A35. As KPC loses business, it will charge more for its products to stay afloat, hence the ever rising cost of petroleum products.

R35. This is not correct as addressed in R32.

A36. The deal only ended up creating irregular supplies and higher prices. Open tender system allowed for competitive sourcing of fuel. Monopolistic tendencies for purposes of maximizing profit goes against demand for efficiency and need to lower prices.

R36. This is not correct. Kenyan supplies are planned two to three months in advance and deliveries are known way before. Contrary to the statement, there has been no disruption in supplies under G-to-G compared to previous systems. Supply disruptions were experienced under the previous system, due to the challenge of accessing forex and prompt payment terms under the then supply regime.

A37. It is going to drive a number of oil marketing firms out of business, leading to job losses and loss of revenue for the government.

R37. This is not correct and the publicly available statistics on the number of OMCs during the G-to-G period has not reduced; on the contrary the number of active OMCs has increased; thereby increasing the tax revenue and employment.

A38. The deal has excessively high Freights and Premiums compared to those witnessed in Open Tender Systems. They are as high as an additional $50 dollars per metric tonne.

R38. The fixed freight and premiums have cushioned Kenya against price volatility while ensuring security of supply with an extended credit period from 30 days to 180 days.

A39. In the end, Kenya is losing billions of shillings in taxes because the three companies picked to spearhead this deal do not pay the 30 per cent corporate tax.

R39.This is entirely untrue, inflammatory, purposefully misleading and is geared to paint the three companies in bad light. None of the three companies have been exempted from corporate taxes and they are all tax compliant. The data and the amounts that the three companies have paid for various taxes, including but not limited to excise taxes, import duty, corporate taxes, PAYE etc. can be easily ascertained.

As noted above, it is a requirement under the Petroleum Act that an Oil Marketing Company must obtain a Tax Clearance Certificate in order to be issued with or to renew its Import Wholesale and Export Licence for Petroleum Products.

Signed at Nairobi on November 17, 2023

Gulf Energy Limited Galana Energies Limited Oryx Energies Limited