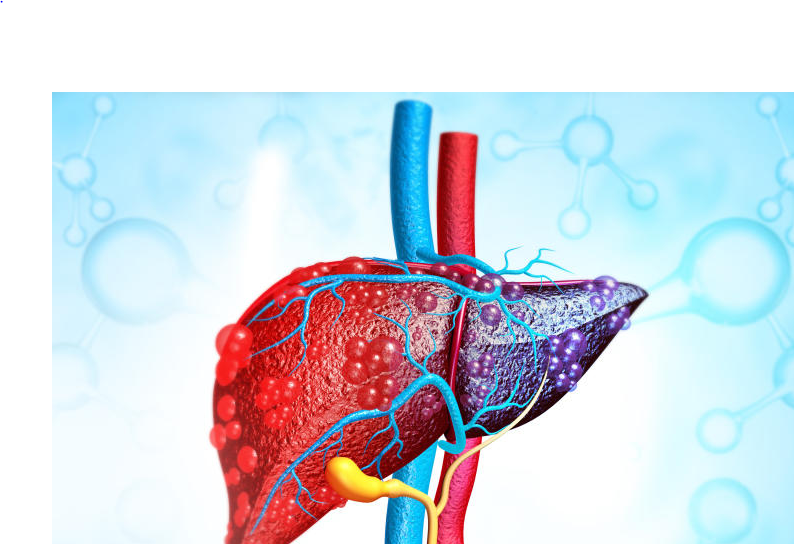

Autoimmune hepatitis quietly damages the liver for years before symptoms appear; specialists in Kenya warn of late diagnoses and urge early medical checks. [File, Standard]

×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

When people think about liver disease, they imagine issues caused by drinking alcohol or infections like hepatitis B or C.