×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

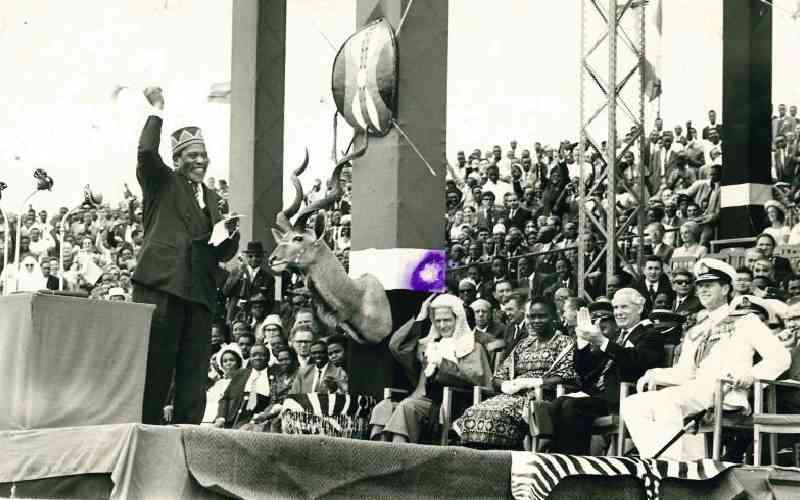

This election cycle has brought to light the issues of class and economic access in our country. Nearly 60 years after independence and numerous elections we have still seen familiar faces contesting for political seats and the presidency.

Our political elite have been in power for the past 20 years since the election of Mwai Kibaki in 2002. During these past 20 years, many of these politicians have leveraged their positions of leadership and political power to amass huge sums of monetary wealth and assets.