×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

The idiom originated in modern Turkey. [Courtesy]

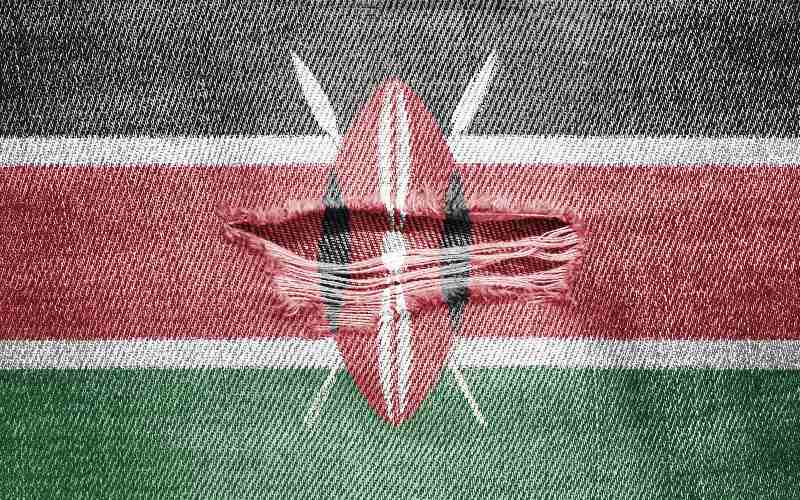

Kenya’s professional civil service and uniformed police (and military) are formidable barriers to mass clientelism. The “unelected bureaucrats” ensure the elected leadership carries out the people’s will in a democratic manner and according to rules.