For those separated from their families or who risk losing their jobs after the government implemented restrictive regulations to curb the spread of Covid-19, last week’s news from Afya House could not have been more ominous.

An average of 60 people tested positive for the coronavirus disease daily over the week.

It was alarming - and worse was yet to come, warned Ministry of Health officials. They projected the peak period when daily infections surge to 200 cases would be in August to September.

Yesterday, 72 new cases were announced, taking the country’s Covid-19 tally to 1,286. Perhaps the dusk-to-dawn curfew, partial lockdowns and social distancing rules are only likely to be enhanced.

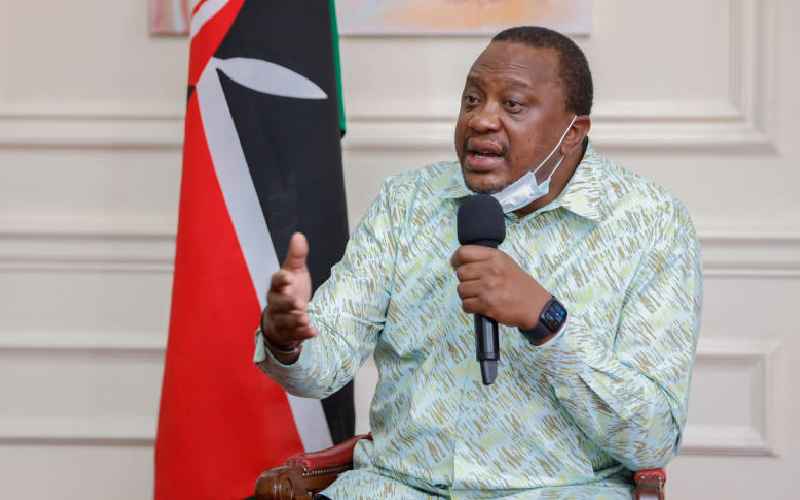

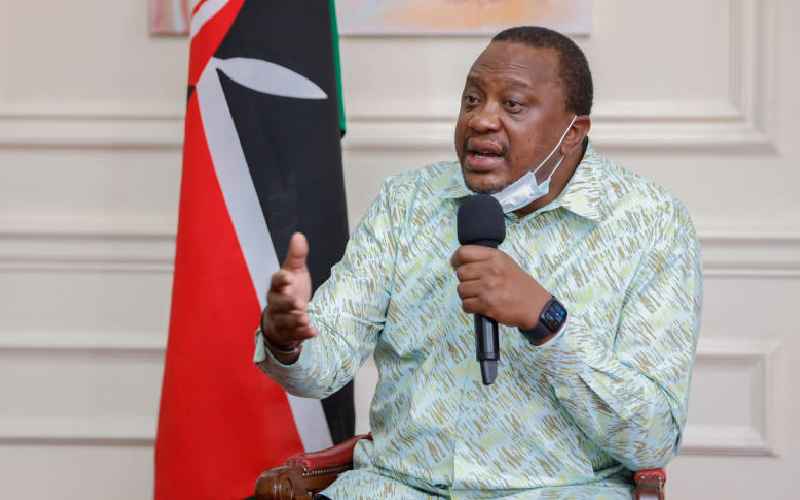

But on Saturday, President Uhuru Kenyatta (pictured) hinted at partially re-opening the economy.

This is at a time when infection rates are approaching the peak of the curve, and Health Cabinet Secretary Mutahi Kagwe is irked by a resumption of economic activities.

Act of survival

It was an act of survival for the Commander-in-Chief who has been forced to choose between letting his citizens adapt to the deadly viral disease or perish from hunger.

And it is not like things will get back to normal anytime soon.

“The coronavirus pandemic will continue undermining our efforts to revitalise the economy for the unforeseeable future,” said President Kenyatta.

But he knows all too well that the effects of freezing the economy for too long would be quite dire. And with the virus spreading, the risks are not just medical. It’s choosing whether to let people die so the economy can reopen, or to retain a lockdown to save lives.

Already, the virus has killed 52 people.

Uhuru finds himself in a Catch-22 because as cases surge, he needs to restrict the movement of people so as not to overwhelm the country’s health system, avoiding an Italy-like situation.

But in the meantime, the staggering toll of unemployment has reached more than four million in just two months.

Businesses are shutting down, aircraft rust in hangars, hotels, pubs and flower farms have since shut down. Millions have lost their livelihoods.

Uhuru might need to follow the example of many other African countries like South Africa and Ghana that are re-opening.

South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa plans to ease restrictions from June 1, which will mean lifting curfew orders, allowing more businesses to reopen and restarting schools. The country has recorded more than 22,000 cases and 429 deaths.

But lifting lockdown measures is not an easy decision – Mr Ramaphosa himself has warned his citizens that Covid-19 cases are likely to get much worse.

“If you open up and people die or get more infections, you are blamed as a leader,” says Gerrishon Ikiara, an economics lecturer at the University of Nairobi.

For Kenya, should the stringent containment measures spill over into the second half of the year, economic experts have forecast, the size of the economy economy will shrink drastically.

The monetary value of all the goods and services produced by the end of 2020, or the gross domestic product (GDP), will reduce by Sh974 billion, according to the World Bank.

McKinsey, a management firm, puts the contraction of GDP at Sh1 trillion in a worst-case scenario.

A slump in productivity is the result of machines going mute in factories, half-open offices and hotels, empty airports and half-full matatus – it means more people at home than work.

Dr Ikiara reckons that the president only implied that if figures of infections and death come down significantly, opening up would be considered.

“In other words, it is not permanent,” he said.

But there is a case for reopening as much as there is for closing, according to the economist, especially considering that a large number of people across the world live from hand to mouth.

“So when you are locked down and you don’t have savings that you can fall back on, it is a crisis,” said Ikiara.

A prolonged period of curfews and lockdowns had already started engendering a feeling of disillusionment.

The rumbles of empty stomachs and eerie taps by landlords on doors for rent from broke tenants have seen millions of self-employed Kenyans scamper back to their work stations.

Data from Google, which has been tracking mobility during this period, shows that the movement of people from home to workplaces had started to go up, to the chagrin of health officials at the forefront of flattening the infection curve.

It only makes sense as unemployment skyrockets. The number of adults who were either actively looking for work or were simply economically inactive shot up by four million to 10.9 million in April compared to seven million in December last year, according to official data.

If you remove students, sick people and those who are simply idle, the number of people who were actively looking for work increased by one million, according to an analysis by Equity Bank.

A big chunk of the jobless people, noted a household survey by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) struggled to pay rent on time in April. And nearly all of them were not aware when they would return to work.

The government, which is expected to do most of the weight-lifting to avert an economic crisis, has started collecting less in taxes.

Cheap loans

Although it received cheap loans of close to Sh212 billion in two months from the World Bank, IMF and the African Development Bank (AfDB), tax collection in April went down.

Last month, Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) collected Sh120 billion compared to the Sh140 billion it managed in April 2019.

Even worse is how the virus has exacerbated inequalities, with its adverse economic impact hitting women and poor workers hardest.

The virus is widening the income gap between genders, and driving the poor deeper into poverty, while the rich either remain where they are or, as has been seen among the world’s billionaires, getting richer.

Compared to August last year when slightly over half of the working population were women, by April, more than half of the women aged 18 and above were jobless compared to a third of men, an analysis of official data shows.

Another survey by audit firm KPMG and the Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM) shows that 40 per cent of manufacturers had laid off casual workers.

Millions of women and the poor in vulnerable jobs, such as bartending, manual labour, hairdressing and driving, have lost livelihoods.

A majority of permanent employees might have escaped the chopping board, however, with the study by KPMG and KAM indicating that employers retained seven out of 10 of these workers.

However, their bank accounts have been running out of cash as salaries are slashed. Left with little disposable income, many of them have raided their retirement kitties, official data shows.

They have also sought to restructure their loans, with data from the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) showing that by April, banks had extended the payment of personal loans worth Sh102 billion.

Most of these personal loans are given to permanent employees with payslips.

However, even those who still have their jobs might not have them for long. According to the KPMG-KAM survey, to survive this downturn, eight out of 10 employers intend to cut costs by downsizing.

If the wave of disillusionment that has been occasioned by Covid-19 is not addressed, reckoned Uhuru, it might degenerate into social disorder.

The head of State noted that while Kenya’s largely young population gave him hope in dealing with the disease, it was also worrying.

“Worrying because during a pandemic like the one we have, the sheer energy of our young population will fight the virus, alright. But in the process, their energy could also be misdirected.”

White-collar crimes might have gone down, but petty crimes such as housebreaking, especially in slums, have been on the rise. Police have also noted increased cases of thugs impersonating law enforcement officers to break into people’s homes.

The long-term effects of keeping children from school are also grim. While this might be the right choice now, experts say there are heavy costs on children’s development, their parents and the economy.

Poor children without electricity at home, leave alone the internet that has been powering online lessons, have suffered the most.

The KNBS survey showed that while 43 per cent of families with schoolgoing children used homeschooling as a coping mechanism during this period, 24.6 per cent of households with members who usually attend any learning institution were not using any method to continue with learning.

Mental illness

United Nations experts have also warned that a mental illness crisis is looming as millions of people worldwide are surrounded by death and disease and forced into isolation, poverty and anxiety by the pandemic.

Frank Njenga, a psychologist, said after the world has flattened the curve of this virus in terms of causing death and disability, the next curve will be that of mental disorders.

“What is interesting is the argument that it is precisely the things that we are doing to try and protect our physical health that are preparing the ground for the epidemic of mental disorder,” said Dr Njenga.

According to him, it is, for example, very unnatural to stop people moving from point A to point B, or telling them not to bury their dead in line with their traditions.

The other consequence of Covid-19, said Njenga, is that it has seen cases of domestic violence spike as couples spend more time together.

“WHO (World Health Organisation) is also saying the world is going to a recession, and you know that poverty and mental disorder come very near each other.”

But Uhuru might also have learned from his African peers who have started to partially reopen their economies after citizens were overwhelmed by “lockdown fatigue”, according to a recent Bloomberg article.

In Ghana, President Nana Akufo-Addo famously quipped that while they knew how to bring back the economy, they did not know how to bring back dead people.

Now, leaders fear that a loss of livelihoods might reach crisis levels, and they have begun to re-open.

“Tens of millions of people across the continent were already in vulnerable situations before this,” Leena Koni Hoffmann, associate fellow of the Africa programme at Chatham House in the UK, was quoted as saying by Bloomberg.

“The cure for the pandemic, especially in African economies, is worse than the virus itself.”

But, generally, the world economy has begun to reopen.

North America, China and Europe, which had been devastated by the virus much earlier than African nations, began to partially open their economies after making headway in reducing infections.

But this has left Kenya and many other African countries, which were hit with the virus much later, in some sort of a fix.

The reopening of these markets presents an opportunity for Kenya to ramp up its production of flowers, tea and coffee for export to these countries.

It is a boon for the flower industry, which has been devastated by the pandemic as demand in Europe plummeted.

Businesses, which Uhuru expects to maintain most of the social distancing rules to curb the spread of the disease, might be tempted to tweak them so as to meet the surge in the export markets.

WHO’s warning that the virus may be here to stay might also have informed Uhuru’s decision to reopen the economy. According to the UN body, people should learn to live with it just as they have learnt to live with HIV.

Taking precautions

But with a vaccine not expected any time soon, countries are reopening cautiously.

Such precautions as washing hands, keeping physical distance, wearing masks, reckons Uhuru, will be with us for a while yet. Security guards at the entrance of your office might still retain their thermometer guns and sanitisers.

Some workers might continue working from home for the rest of the year, or like Twitter’s employees, forever.

Nelson Gitonga, a health economist, said there is a need for gradual reopening of the economy.

“Unless you give them strong safety nets, you can’t keep them at home for long. It reaches a point where you have to balance between the risks of infections vis-à-vis people dying of hunger and also social upheaval,” said Dr Gitonga, vouching for easing of the lockdown while maintaining the night-time curfew.

He also does not think curfews, pubs, schools and public service should resume normal operations.

Two things, Gitonga said, could happen: “The epidemic could shoot very high and our hospitals are overrun with sick people, and that will be a lesson by itself; or the infections could increase, but a majority of the infections could be less severe or asymptomatic, with people developing some level of herd immunity.”

After all, explains the health economist, the whole point of flattening the curve has to do with avoiding overrunning the country’s weak health facilities with very many sick people all at once.

Meanwhile, Uhuru’s intention is to kill two birds with one stone. Most of his recently announced Sh53.7 billion economic stimulus package is not only aimed at curbing the spread of Covid-19, it is also aimed at creating jobs and injecting cash into the economy.

Uncover the stories others won’t tell. Subscribe now for exclusive access

- Unlimited access to all premium content

- Uninterrupted ad-free browsing experience

- Mobile-optimized reading experience

- Weekly Newsletters

- MPesa, Airtel Money and Cards accepted