×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

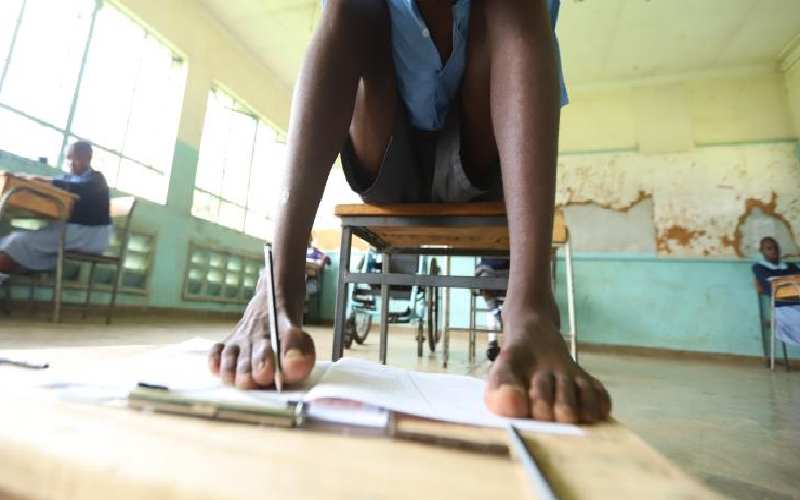

There is so much hype about home schooling during this time when Kenya, like all other countries, is responding to the Covid-19 pandemic. The use of education-related ICT innovations that would have otherwise struggled to be recognised has gained momentum.