×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

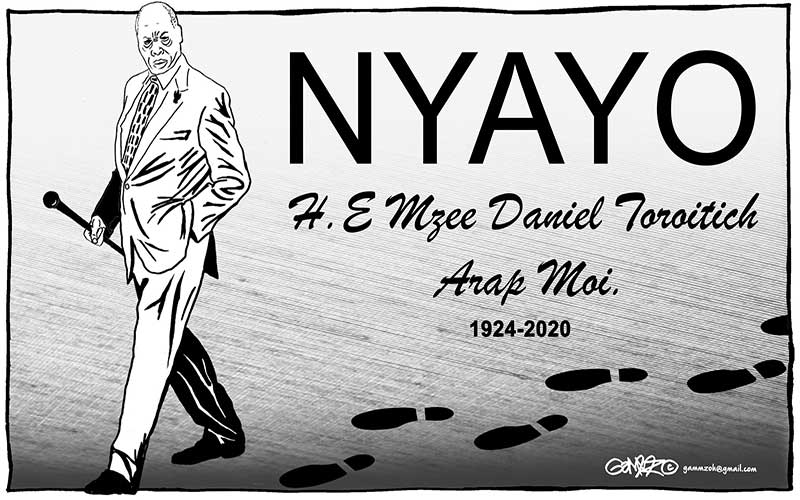

In his nearly five decades of public service since joining the Legco as a Rift Valley representative in the mid-1950s through to when he surprised both friend and foe by leaving the presidency when it was anathema for Africa’s big men to do so, President Daniel arap Moi has left an indelible imprint and affected the direction of the nation in the most profound of ways.