×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

For the first time since it won independence from Britain in 1966, Botswana faces a genuine electoral contest on Wednesday, as a feud between its current and a former president throws one of Africa’s most stable nations into uncertainty.

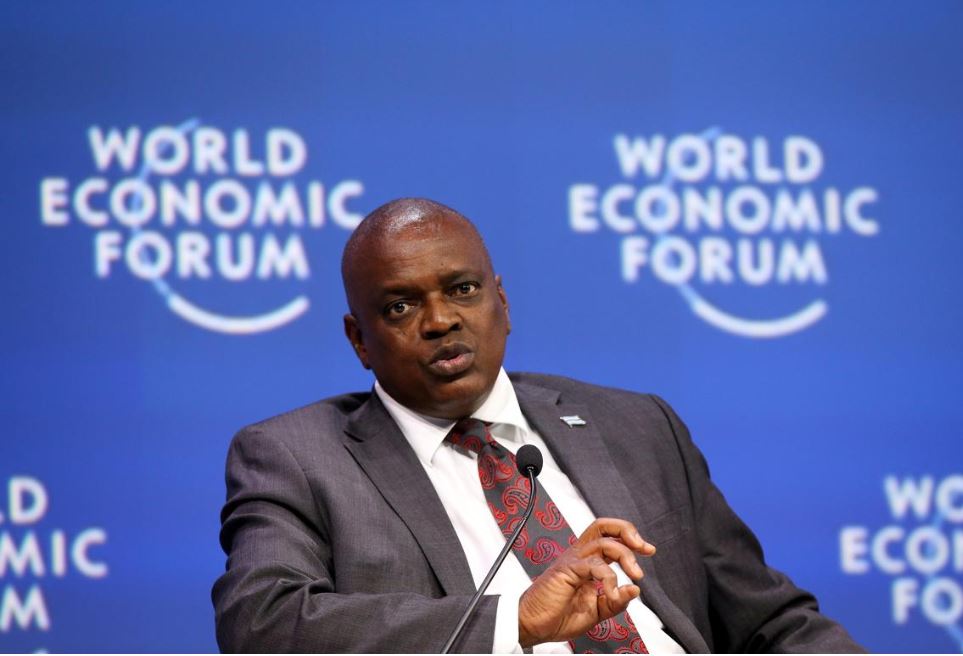

The Botswana Democratic Party, in power since Independence Day, faces an unusually tough parliamentary vote, after the country’s former president and political heavyweight Ian Khama fell out bitterly with his hand-picked successor, President Mokgweetsi Masisi, earlier this year.