×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

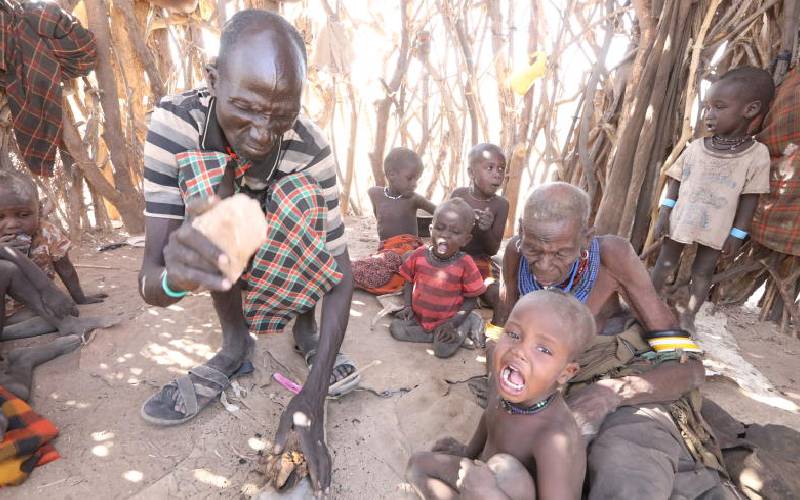

Hunger stricken Ang'emoi Lochoro feeds his mother Nakiri Lochoro and children roasted camel hide at Kapong' village in Turkana County. Many people and livestock have so far died due to the famine ravaging Turkana County. [Photo, Kevin Tunoi]

Kapong village appeared deserted on the scorching hot afternoon that The Standard team visited.