×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

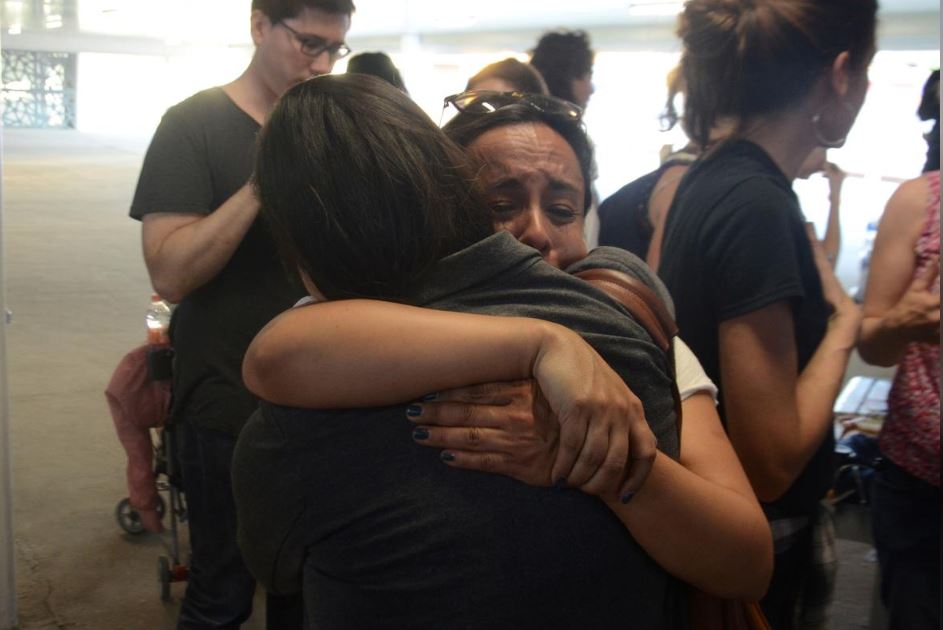

A large group of Central American migrants who US authorities separated from their children last year when they crossed the Mexican border entered the United States again on Saturday asking for refuge and to be reunited with their kids.

A Reuters witness said some 50 people entered the United States at the international border crossing from Mexicali, Mexico into Calexico, California, where they were met by agents from US Customs and Border Patrol (CBP).