×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

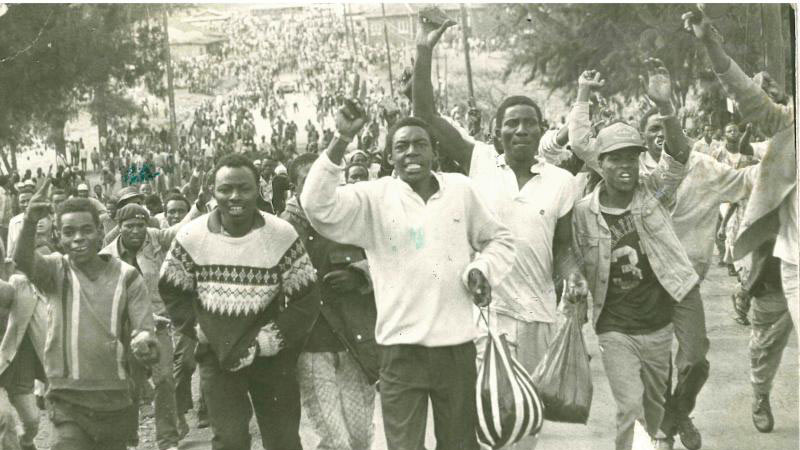

Sometimes in 1990, two political ‘dissidents’ went to Cargen House in Nairobi’s Moi Avenue.

Controversial former Kitutu Masaba MP George Anyona and his neighbour in Madaraka Estate Njeru Kathagu’s mission was to rein in a man disgraced by the ruling party Kanu and thrown into political cold.