×

The Standard e-Paper

Kenya’s Boldest Voice

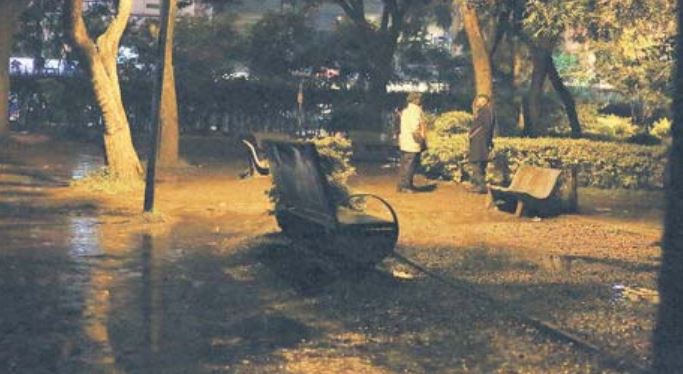

On a chilly Tuesday afternoon at Nairobi’s Jeevanjee Gardens, a preacher stands on one of the paved walkways and belts out a gospel song.

His voice rises higher, accompanied by several uncoordinated dance moves. He punctuates it with outbursts, declaring that he has an urgent message from the Lord.