×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

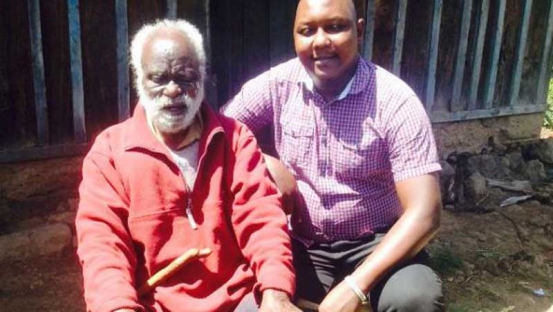

For 95-year-old Chelestino M’Mwirebua, the drums of Mau Mau war and the trumpets celebrating independence still ring in his ears to this day.

It is as if the entire struggle for independence and the eventual triumph happened just yesterday.