It is shameful that the world’s poorest children remain nearly twice as likely to die before their fifth birthday. An unconscionable majority die unnecessarily. Most of these deaths could have been prevented with cheap, but effective interventions.

Today, UNICEF is launching a compelling report, Narrowing the Gaps: The power of investing in the poorest children, showing that investments in the most deprived children and communities provide greater value for money. The study indicates that every $1 million invested in the poorest children saves nearly twice as many lives as the same investments that do not reach the poor.

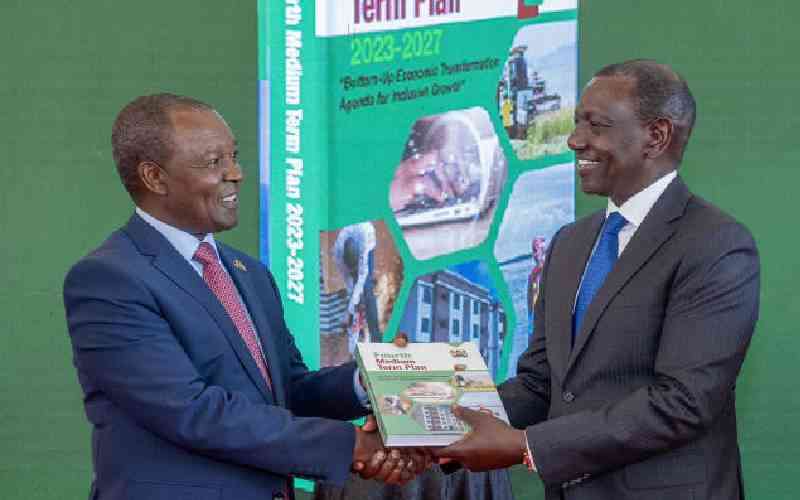

These findings have important implications, also here in Kenya, especially as the Government works to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Kenya’s Vision 2030. The SDG child mortality target aims to end all preventable newborn and child deaths by 2030. This universal goal demands urgent action to reach the still unreached children, families and communities.

The UNICEF study looked at the difference in reaching poor and non-poor children with six critical health interventions, as well as at the rate of increasing coverage rates across 51 countries.

It included more than 400 million children under the age of 5. Data for antenatal care visits, skilled birth attendance, early initiation of breastfeeding, use of insecticide-treated bed nets to prevent malaria, full immunisation and care-seeking for sick children were analysed.

There were three key findings. Poor children are less likely to be reached with these interventions; coverage improved over the past 10-15 years for both poor and non-poor children; coverage increased most among poor children. It showed that access to basic high impact health and nutrition services have narrowed considerably compared since 2010.

The 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey confirmed progress in reducing child under-five mortality rate: it was 52 per 1,000 live births, down from 74 per 1,000 in 2009, with significant decreases in child deaths from HIV, malaria and measles.

Impact of mortality rates

This is directly linked to increased coverage of effective health interventions, including increased use of mosquito nets among children, better immunisation programmes and general improvements in the health system.

The study shows progress can be further amplified if we focus our attention more on the most deprived and vulnerable. Regional disparity in Kenya continues with significantly higher child mortality among populations in arid, semi-arid and rural areas.

For example, 38 per cent of rural households reported that long distances prevented them from accessing health services, compared to 29 per cent in urban areas. Access to skilled doctors and health workers is also widely varied. The doctor to patient ratio in Turkana is 1 to 285,000 compared to the national average of 1 per 7,150 people. This impacts mortality rates for children under 5, where Nyanza region had rates of 142 child deaths per 1,000 compared to Nairobi with 46 per 1,000.

It is therefore important to think beyond national averages, and to pay attention to inequality between regions or population groups, to improve the situation in the country as a whole. It is also important to think about individual situations, what statistics mean for a person or a household, and try and reach every child with important interventions.

Of course, we can’t stop at survival. Without access to quality health care they need, many children who live to see their fifth birthdays will face the lifelong consequences of poor health and malnutrition. High-impact, high-quality health and nutrition services must be made available to mothers and children in poor communities.

This includes little Alamy whom I met with her mother, last week. Due to the current drought, Alamy is one of the over a million children who are food insecure – meaning her family does not know where their next meal will come from. She had walked with her mother and two brothers for hours in the hot sun for over 10km, to receive much needed nutritional supplements at a local health centre.

Tragically, girls like Alamy are not unique. In 2017 alone, at least 100,000 babies and children under five years of age urgently need treatment for severe acute malnutrition, a life-threatening condition. Beyond those who need life-saving help, there are many children who are not in acute danger, but are suffering from impacts of the drought.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Many are chronically malnourished - not getting the right food needed for a healthy development of both body and brain – and robbing them of chances for a bright future.

UNICEF is committed to continue working with the Government to reach the hardest-to-reach. Devolution of responsibilities to counties has meant that decisions can be made closer to the point of need, to girls like Alamy.

There are successes in national and county health policies and programmes refocusing healthcare to meet the needs of their local communities, but more can be achieved. This includes investing in safe water points for families.

Mr Schultink is UNICEF Kenya Representative

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.