By Jesse Masai

The Kenyan Government, wags online continue to suggest, is harping on its flute while the education sector burns.

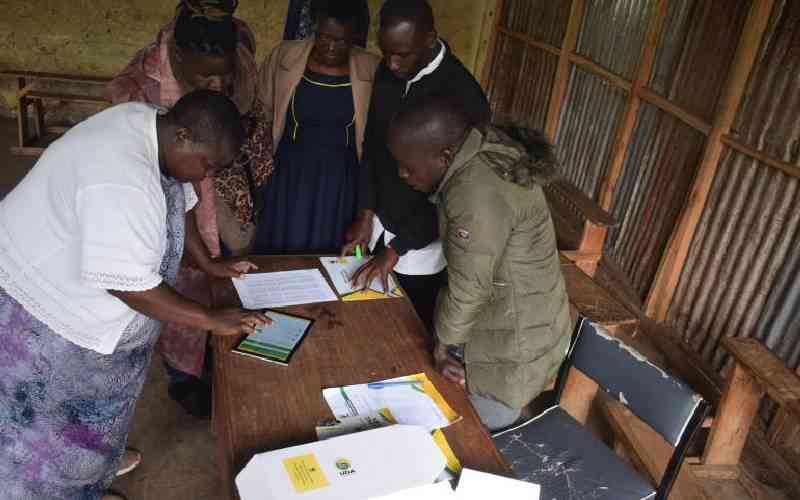

In Trans Nzoia County, reports continue to stream in of learning paralysed by a cartel stealing and exporting much needed textbooks to a neighboring – and, by all official accounts, friendly - country.

In South Africa, there hasn’t been a shortage of criticism over the government’s failure to supply textbooks to schools that need them, in time.

Indeed, a legislator here much wondered how a system that could effortlessly distribute and retail in Castle Lager – their version of Tusker – to the minutest of villages, yet not as vigorously distribute the textbooks. Quite frankly too, there exists an intense and frequent debate on much else that still begs for attention in South Africa’s education sector.

Bread issues aren’t entirely sorted out either, but teachers appear keen to continue eating their chalk.

The teaching profession has been dignified by no less than the parent ministry, what is referred to here as the Department of Education. Sample this pitch that I saw, on a notice board, in a physics high school class in Stellenbosch: “South Africans across the land want a batter future for all. Become a teacher and make this vision a reality in South Africa. Teaching makes a difference. Apply for admission at a university of your choice. Contact the university’s Financial Aid office about the Fundza Lushaka Bursary for Teaching. Visit this website for more information: www.education.gov.za”.

Am not certain how those handling the education in Nairobi might best sex up the sector, but their counterparts here seem to have found a way to make teaching attractive to younger minds.

Teachers, in the post-apartheid era, are keen to raise a generation that integrates values with learning.

A direct consequence of this in a school I have visited in Stellenbosch has been pupils driven by excellence, integrity, respect, bonding, trust in God and unconditional acceptance of self and others.

The “God’ bit doesn’t particularly excite some, but results are there for all to see in the high enrollments, excellent performances in and out of the classroom, and holistic formation of young minds graduating in the end.

In another school – the one that had teachers being courted from a physics class – a teacher has understood father-son relations as having a direct impact on the quality of learning among his pupils.

He considers restoring effective fatherhood – via training and support – as being central to strengthening the nation’s strained social fabric. Schools, he believes, are the most central entities within communities. This understanding has led him consider a school’s function as a place of encouragement, support and equipment of fathers, spawning an initiative that is gaining traction with many families (see: www.engageschools.org ).

As may be expected, mothers are dying to be part of the conversation; faced with the reality that they are not welcome, they are pushing their husbands to go with the sons, and engage on everyone else’s behalf.

In historically black and colored schools, others are reaching out with similar, localized efforts. How many of us go through Kenyan schools tapping into such initiatives is anyone’s guess, but it really cannot for long be a preserve of just a few, or the best equipped. It cannot also for long be the thankless task of the few dedicated state and non-state actors in our slums, and far-flung villages.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Our fathers, too, must recognize that fatherhood goes beyond mere conception; our mothers cannot for long remain our beasts of burden, without consequence. Our teachers, hopefully, will come around to the thinking that the task cannot be outsourced to that visiting speaker, or motivational group.

Critically, the State ought not to be allowed to – in any way – walk away from what that famous Galilean, Jesus, once referred to as “the least of these.” Once too often we’ve allowed it to walk away, because of “insufficient funds,” while there’s much to spare for black holes in the budget.

Our children’s plight is, quite narrowly, often reduced to case studies in sex tourism at our coastal cities, but so much more also remains untold from Naivasha, Nakuru and our other villages and towns.

The writer is a media consultant, based in Cape Town, South Africa.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.