|

|

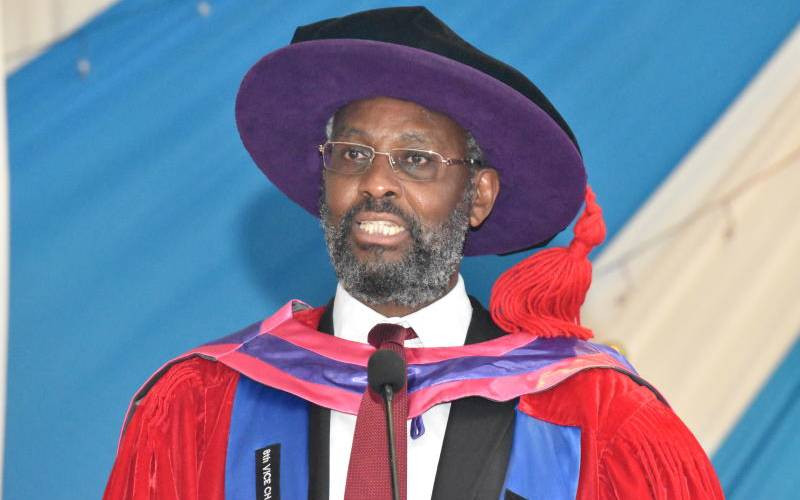

Prof Taban lo Liyong. [Photo Courtesy] |

By PETER KIMANI

I must declare from the onset that I feel conflicted writing about Prof Taban lo Liyong: I revere old age and, at 77, he deserves my respect. Secondly, our lives have intersected socially and professionally over the years, and we have many common friends.

But since Taban does not respect his age by bearing fidelity to the truth, it would be remiss to recuse myself from exposing the intellectual fraud that he continues to propound, his target of choice being the venerated Kenyan author, Prof Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

Taban’s tirade in Saturday Nation last week crosses the line because of the falsehoods that he presents in his bid to denigrate Ngugi’s literary legacy.

More deserving than Ngugi

He told Saturday Nation jua kali artisans would be more deserving than Ngugi. That would be an interesting question for contemplation, if only proper parallels are established to connect the two creative endeavours.

But Taban offers none of that. His crude conclusion that jua kali artisans, hopefully in Gikomba, hewing sufurias and jikos from hulks of metal have impacted the world better than Ngugi’s writing was expected to stand simply because Taban says so.

After all, Taban lo Liyong is about Taban lo Liyong.

I will respond directly to the slander and historical revisionism that Taban cynically presented in that article, and dispel the litany of lies that if allowed to stand, might be misconstrued as truth.

“The farthest I have followed Ngugi is when I read The River Between, which is a rendition of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, and A Grain of Wheat — by far his best creation, a classic,” Taban charged. “But then he (Ngugi) went down socialism and wasted a lot of time trying to become a political leader…”

Let’s pause there. A Grain of Wheat came out in 1966. So if Taban has not read Ngugi for the past 47 years, during which he has produced dozens of titles, what rational logic would propel him to assess that which he doesn’t know?

I was about to say hubris but I checked myself just in time.

I will try to be respectful on account of Taban’s age.

Texts in conversation

On The River Between, which came out in 1964, Taban says it is a “rendition” of the late Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

Certainly the two texts are in conversation – literary allusion is the term – as they both deal with the disruptions that British colonialism unleashes on two African communities, one in Central Kenya in the 1920s, the other in Nigeria in the 1880s.

I wonder what crime Ngugi could have possibly committed by writing the book. I have no idea what Taban means by “he (Ngugi) went down socialism (sic) and wasted a lot of time trying to become a political leader…”

Since Taban confesses to being in the habit of talking to himself I can only assume he was talking about his own quest for political power. He had a stint as a Member of Parliament for Kajokeji in South Sudan. Ngugi, as far as I know, has not contested any political office in Kenya in his 75 years.

Taban goes on to confess: “I don’t know whether there is anything deeper in his (Ngugi’s) new books.”

Alas! If Taban can still read, he will be pleasantly surprised to find Ngugi’s recent offering, Globalectics: Theory and the Politics of Knowing, is partly dedicated to him! “In memory of the late Henry Owuor Anyumba and for Taban lo Liyong…” reads the dedication, “Fellow authors of the 1969 statement…”

A brief context: On September 20, 1968, Dr James Steward, then acting (British) head of the Department of English at the University of Nairobi, previously a satellite college of the University of London, issued a communique setting out the university’s futuristic plans.

His plan situated English language as the focal. Subsequently, Ngugi, Taban and Anyumba wrote an internal memo in response, what’s now broadly identified as the Nairobi Revolution because it instigated monumental change in the Kenyan academy and beyond.

Ngugi, Taban and Anyumba demanded the scrapping of the Department of English, arguing the new political dispensation in Kenya demanded a rethink on the kind of literature that would be relevant to Kenyan students.

Study of African Literature

In their estimation, the three wrote, the proposed “study of the historic continuity of a single [English] culture” undermined legitimate study of African literature, which should have been at the core, not the periphery of an African university.

Moreover, the three wrote, the entrenched position of the English language in colonial education meant it would extend its domination in the newly independent states, reducing Africa to an extension of Western cultural hegemony.

Since then, Ngugi has published extensively on the question of power and language, producing at least a dozen books of critical essays and literary and cultural theory.

Of the 1969 initiative, Taban cynically undercuts the trio’s achievements and casts it as a lost cause.

“We left the war half-way, a war we did not win in 1969. We did not produce captains to complete the war,” he told the Saturday Nation last week. “We were really amateurs. We were just writers. None of us was a literary scholar. There was no intellectual solidity. We were just promoters of literature, but not really professionals.”

This is plain tosh. The internal memo that the three produced is now an inaugural statement in postcolonial literary criticism. More immediately, the University of Nairobi acquiesced to the trio’s demands and the English Department was replaced by a Department of Literature incorporating oral literature, African diasporic literatures and writings from Francophone and Lusophone Africa.

The legacy of that campaign also altered the way literature is taught in Kenyan schools, and it influenced, and continues to influence societies that seek to indigenise knowledge production.

Wind of change

As Ngugi acknowledges in Penpoints, Gunpoints and Dreams, the 1969 memo provided the “first shots” – a fitting metaphor for their aggressive onslaught – but clarifies their campaign did not propose a scrapping of the Department of English at Nairobi but its reorganisation.

Further, he elaborates this was part of the broader wind of change then sweeping across East Africa, fronted by Grant Kamenju at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania and linguist Pio Zirimu at Makerere University in Uganda.

Ngugi distils this argument in Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature, now a primary text in post-colonial studies across the world. But of course Taban wouldn’t know this since he has not read Ngugi since 1966.

Ngugi’s latest collection

Globalectics takes the argument further, and Ngugi’s latest collection of essays, In The Name of The Mother: Reflections on Writers and Empire, rolls off the press this week in London.

All Taban’s milestones – good books other personal accomplishments – came and went in the 1960s. He reminded the Saturday Nation that he was the first African to graduate from the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

That’s very true. He still holds that distinction. He left Iowa in 1968. I went there 40 years later. Unsurprisingly, Taban was very well remembered by those who knew him then – but for other things besides writing, although he claimed he would write for 36 straight hours in Iowa. The Saturday Nation recorded he was imbibing dry shots of vodka – I think he said he likes them in doubles – late into night. Now, we got an inkling of what Taban can manage without interruption!

But the singular endeavour in which Taban has succeeded spectacularly, and for which there is ample evidence, is that he is sorely envious of his more famous peers.

Listen to him: “Nobody has studied my books to interrogate me since 1965. Nobody has followed the arguments; I am always explaining myself. I feel that I have not been taken seriously. I am frustrated. I feel let down,” he said in that interview.

That makes perfect sense.

Not only has Ngugi continued to produce works of outstanding merit, they also continue to be widely read and studied.

In a career spanning nearly 50 years – he celebrates the milestone next January – he has produced about three dozen titles, which have been translated into as many languages.

Lifelong endeavours

That’s why next month, the Nobel Committee at the Swedish Academy might, and I hope that they do, crown his lifelong endeavours with the Nobel Prize for Literature. He certainly deserves it. His work speaks for itself, at least to those who read him.

I wanted to say I found Taban’s comments on Ngugi base and crass. But once again, I shall be respectful and employ restraint.

Instead, I shall use the metaphor Taban supplied to speak about himself. He says his “self-appointed job is to point out that the king is naked, if he is.” The metaphor is very appropriate, for King Taban lo Liyong, indeed, is naked.

Writer is a ‘Standard’ columnist and novelist. He is presently a teaching fellow and doctoral student at the University of Houston’s Creative Writing Programme.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.