×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

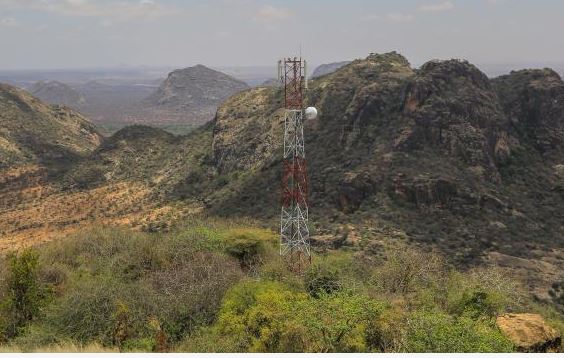

Residents of Ngurunit village in Samburu County will no longer have to walk for three kilometres whenever they want to make phone calls because of a weak signal.