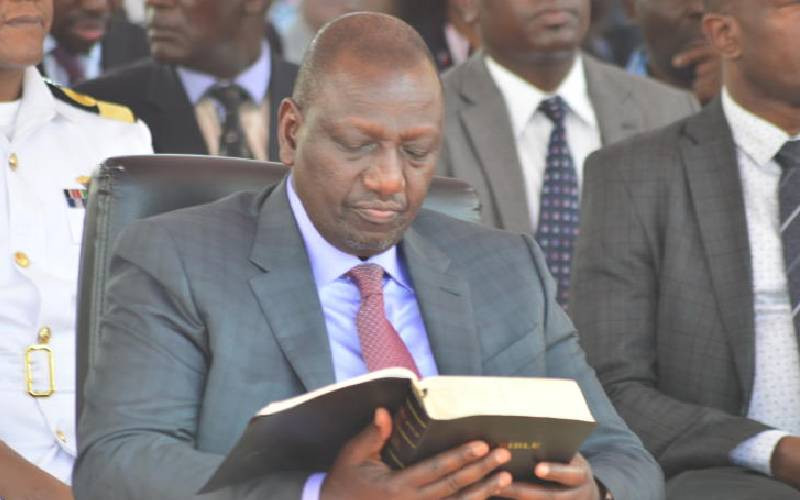

The narrative of God winning Kenya's elections should have died by now. But this "God won" doubled with "We won" narrative keeps resurrecting. In some church corridors, it has evolved into a tagline that has been exported to political podiums.

Beyond the light-darkness spiritual warfare understanding, the "We won" is also being used along church corridors to paint shades of light. The muscle flex is on between modern and traditional church formations. In political podiums, this punchline is being used to punch the opposition. The "God-won We-won" slant is serving to stamp an otherwise worldly endorsement of the present administration.