×

The Standard e-Paper

Stay Informed, Even Offline

NAIROBI: Plans to collapse the Jubilee coalition parties into one outfit marks phase one of the re-construction of Kikuyu-Kalenjin dynasty arrangement that ensured Kanu ruled Kenya for 36 years.

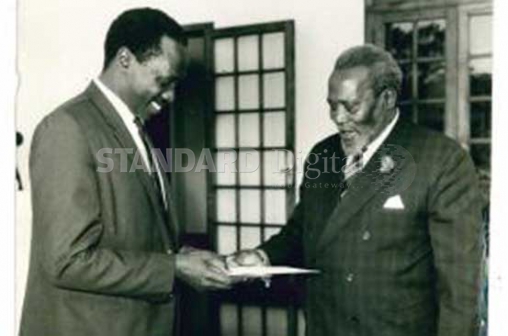

The consolidation of the Mt Kenya and Kalenjin voting blocs under the newly-launched Jubilee Party marks a major milestone in the re-enactment of unusual parallels between Mzee Jomo and Uhuru Kenyatta in acquisition and retention of political power.