×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

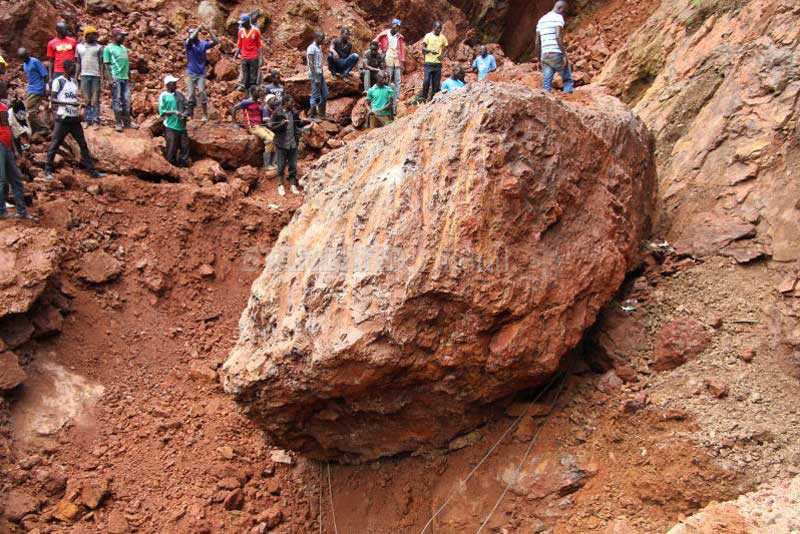

They wake up at the crack of dawn, seven days a week, and spend agonising hours courting danger in the treacherous mines of Nyatike.

Most of the times they return home exhausted and grateful to God for sparing their lives. Sometimes they do not, and instead end up in morgues. Yet for the gold and copper miners of Nyatike in Migori, life must continue.