×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

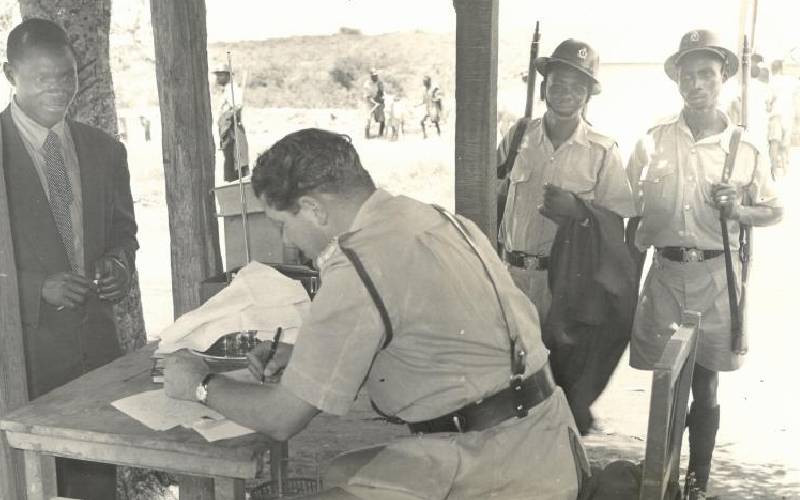

The restive north is aflame again. The military has been dispatched to the 'disturbed and dangerous' counties of Turkana, West Pokot, Elgeyo Marakwet, Samburu and Laikipia.

The world is, however, waiting to see whether the sandals made from car tires will outrun and outfox the military boots.