×

The Standard e-Paper

Home To Bold Columnists

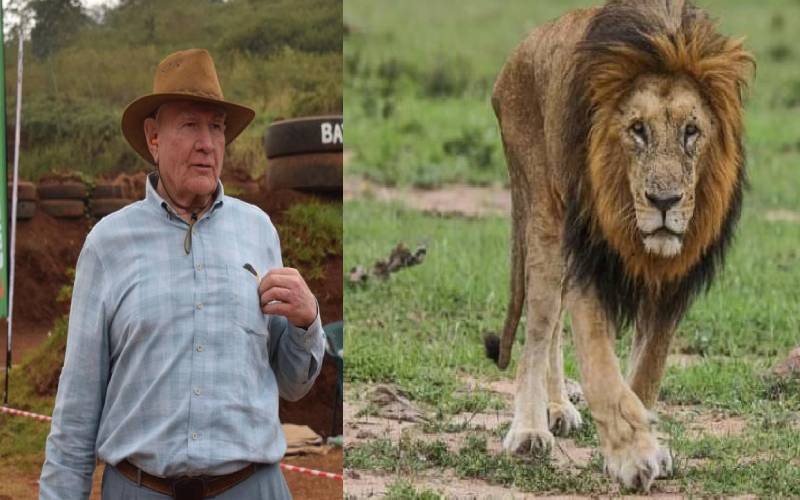

Robert Poole, a game hunter's thrill and nostalgia of gone good old days. [Courtesy, Standard]

Robert Poole, a retiree, does not sit under trees regaling people with stories of his past.