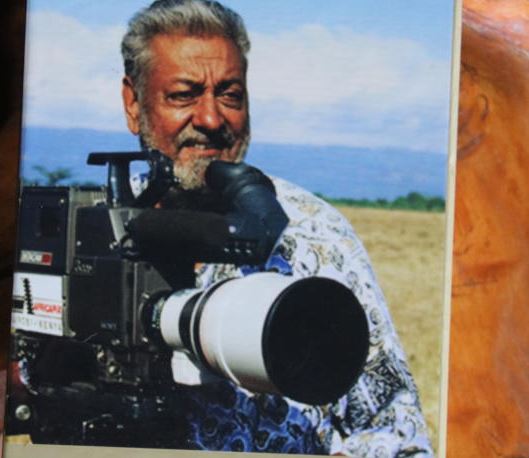

Away from the panicked spraying of disinfectant, the veteran documentary director sat, as if oblivious of Nairobi city, which was in turmoil. Not even the birds happily chirping away in his garden appeared to cheer him. Something almost akin to the ravaging coronavirus, had turned his life upside down and plunged him into deep mourning.

“How can I even smile when I am mourning an exceptionally good man I have known and worked with for 30 years? This man was not just a colleague but a friend. A brother. We have done so much together,” he said.