×

The Standard e-Paper

Fearless, Trusted News

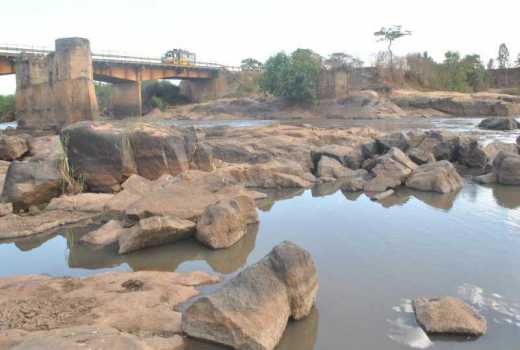

Kenya’s rivers are drying up quickly. From the great Tana and Ewaso Nyiro river – the main source of water for the arid north – to rivers flowing from the slopes of Mt Elgon and Chereng’any hills, the story is the same.

In central Kenya, rivers that previously gushed down the highlands, offering sustenance to millions, are drying.