Kenya, like the rest of the world, faces a formidable cancer care gap that pervades the country’s healthcare system. This void manifests in four critical domains, each crying out for immediate attention. The funding gap, the awareness gap, the healthcare worker capacity gap, and the community support gap.

The fiscal deficit in cancer care is perhaps the most pressing concern, given its potential to alleviate other systemic issues. Despite the growing number of cancer cases, the financial commitment to combating the epidemic remains insufficient. As a result, the healthcare system faces an acute shortage of critical resources, limiting its ability to provide timely and effective interventions.

This situation is exacerbated by a shortage of healthcare workers, a problem many developing countries face. A severe shortage of healthcare professionals with specialised expertise in cancer care has put the healthcare system under strain. According to a recent report from Kenya’s National Cancer Institute, there aren’t enough oncologists, oncology nurses, or oncology pharmacists to handle the disease burden. The growing demand for specialised care far outstrips the supply, resulting in longer wait times and fewer treatment options.

Furthermore, lack of healthcare facilities to handle cancer diagnosis and treatment exacerbates the crisis. Kenya had only 19 external beam radiation machines as of 2022, while 42 were required. Only eight are in public hospitals, contributing to long wait times. Patients who choose private healthcare frequently face prohibitively high costs, posing an additional barrier.

The lack of community support is exacerbated by the public’s lack of understanding of cancer and its symptoms. Cancer is frequently portrayed as a lifestyle disease, making it difficult to dispel the widely held belief that cancer, including paediatric cases, is not always the result of poor decisions.

That said, to address the cancer care gap, Kenya must pool its resources, both financial and human, and work together to bridge these divides. The urgency necessitates a united front from international stakeholders, philanthropic organisations, and governments, fostering a collaborative commitment to bringing about meaningful change.

Gertrude’s Children Hospital, for example, is working to close these gaps through the Kenya Childhood Cancer Programme, which raises funds for free diagnosis and treatment for children all over the country. Gertrude’s raises funds for diagnosis and treatment through initiatives such as the annual run and golf tournament, as well as free training for healthcare workers to better detect and treat childhood cancer cases.

Last year, we covered the cost of treatment for 40 children through these charity initiatives, with the funds also covering incidentals for family members who accompany their children to the oncology center, as well as psychological support.

This year, we are holding the cancer walk in March to raise funds to support children with cancer access diagnosis and treatment at no cost. The walk will be an opportunity for outdoor activity, while contributing to the war against childhood cancer.

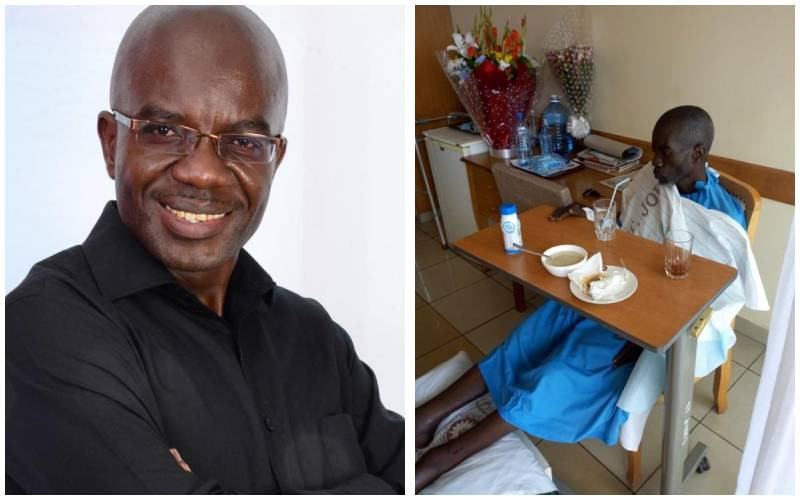

Dr Karimi is a haemato-oncologist at Gertrudes Children’s Hospital

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.

The Standard Group Plc is a

multi-media organization with investments in media platforms spanning newspaper

print operations, television, radio broadcasting, digital and online services. The

Standard Group is recognized as a leading multi-media house in Kenya with a key

influence in matters of national and international interest.