×

The Standard e-Paper

Smart Minds Choose Us

Franklin Mueke moved briskly from truck to truck, chatting with the drivers.

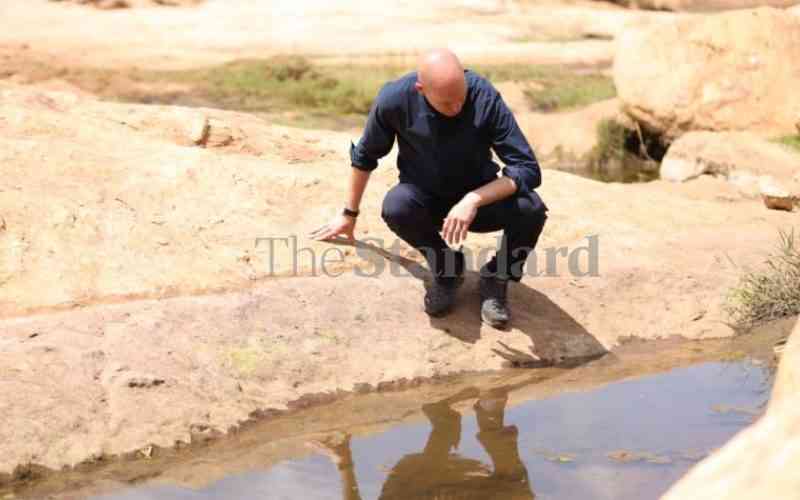

They had parked nearly eighty trucks on River Muooni's sandy riverbank. As one of the few local sand brokers, Mueke was the bridge between sand loaders and truck drivers. Part of his work was to ensure each truck had sufficient loaders.