×

The Standard e-Paper

Join Thousands Daily

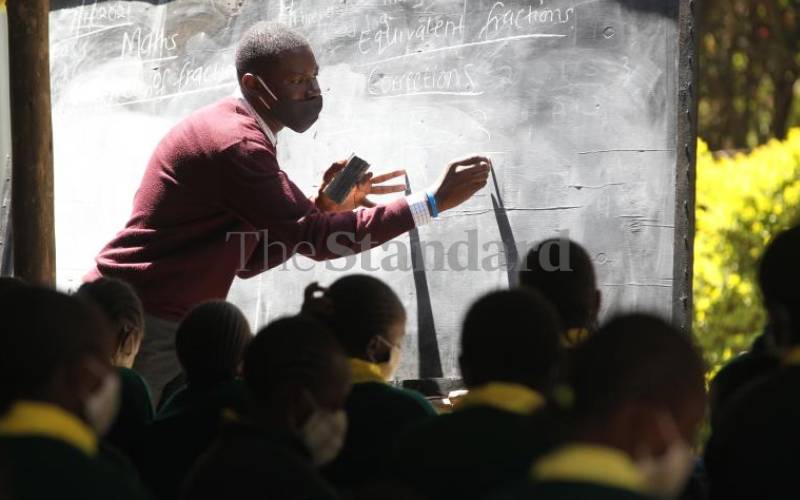

Is the irony lost on anyone that as the rollout of a skill-based curriculum gathers steam, we elect to overhaul a fairly balanced teacher training willy-nilly and replace it with content-heavy training as opposed to a skill-focused one?

The move by the Teachers Service Commission to have the Bachelor of Education (Science and Arts) degrees scrapped from universities has elicited divergent views and strong opinions from education stakeholders.